Point-counterpoint discussion finds common ground on controversial organics bans.

By Thomas Bilgri and Debra Darby

Almost 30 percent of the municipal solid waste (MSW) stream generated in the U.S. is organics, nearly all of which is disposed of in a landfill or waste-to-energy facility. Many states looking to increase their recycling rates have promulgated (or are seriously considering) regulations banning or limiting organics disposal in favor of diversion through composting or digestion.

The diversion debate has engendered a great deal of controversy in the solid waste world. The pro-diversion perspective championed here by Debra Darby, National Organics Manager for Tetra Tech, focuses on the environmental benefits and the opportunities for introducing a more sustainable waste management structure. The other side of the debate, hailed by Tom Bilgri, National Biogas Manager for Tetra Tech, decries the move as yet another costly and unnecessary mandate—leading to reduced revenues and possibly weakening or even destroying existing landfill gas recovery projects.

We review the basic philosophy behind each of the perspectives, look at the infrastructure challenges and costs involved, and then outline an approach that both agree might work. Spoiler alert—it involves combining anaerobic digestion (AD) with the production of renewable, very low-carbon intensity vehicle fuel at existing solid waste management facilities.

Point/Counterpoint

The pro-organics diversion position holds that organics material management1 brings us to a more sustainable waste management structure. The structure results in what is known as a circular economy—one that creates new green economy jobs, new products and a new infrastructure for organics waste management. Closely based on EPA’s Waste Management Hierarchy, the Food Recovery Hierarchy stipulates that there is a better purpose and use for organics than landfilling (see Figure 1). This perspective focuses on increasing policies to reduce food waste through food donation and organics diversion to help build a collection and processing infrastructure that supports organics recycling.

Figure courtesy of EPA.

The diversion-skeptical perspective complains that this approach is another in a long line of solid waste mandates, calling organics diversion driven by feelings rather than need. Nothing suggests that organics diversion will reduce burdens or costs to the consumer—it will only add more government control and layers of bureaucracy.

The main sponsors of organics diversion legislation are environmentally progressive organizations, but it is important to note that current recycling facilities do not make a lot of money. Is the rest of the solid waste industry going to end up subsidizing the organics diversion movement?

Let us not forget that the reduced market for recyclables, coupled with the COVID-19 crisis, is already pushing some municipalities towards reducing recycling—not increasing it. Witness a recent suggestion that New York City could save $185 million a year by eliminating recycling entirely by just sending everything to the landfill.

New Organics Diversion Legislation

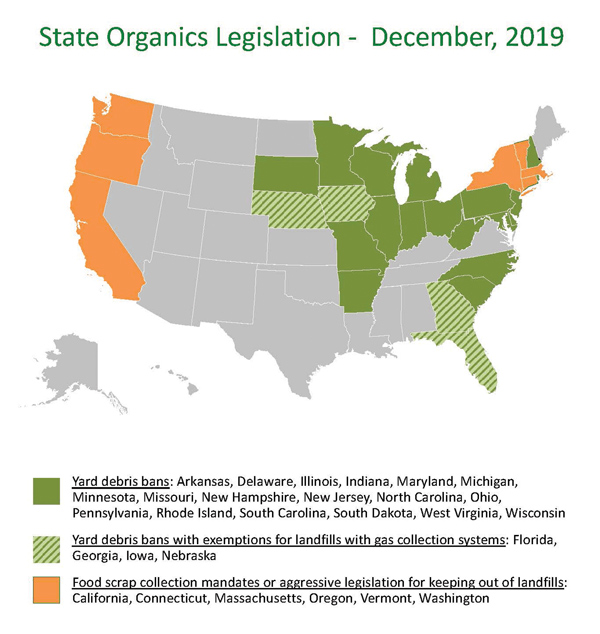

As of December 2019, 22 states have banned the disposal of yard debris in landfills. Four of these states (Florida, Georgia, Iowa and Nebraska) have exemptions for landfills with landfill gas (LFG) collection systems. Seven states have an organics recycling mandate or legislation for diverting food scraps from landfills (see Figure 2).

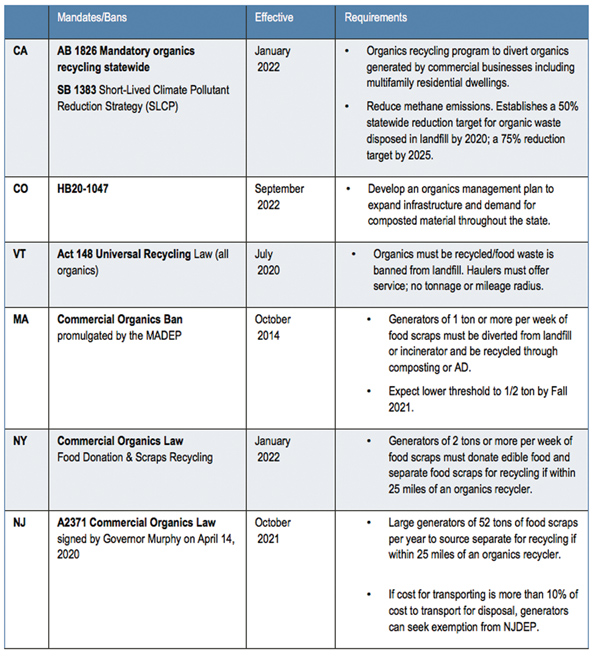

The target for most organics (food scraps) legislation, shown in Table 1, is commercial generators (not residential). The goal is diversion from landfills and incinerators, providing a beneficial use for food waste rather than simply throwing it away.

Food waste bans are typically a function of population density and are most prevalent on the coasts and in the Northeast. They are often in states that are running out of landfill space and where it is tough to site a new landfill, such as Massachusetts, Vermont and New York. The Midwest and South, where there is more available open space, have not gotten on board with organics diversion. In addition, tipping fees in areas with bans are typically higher, due to both space limitations and environmental regulations. (Some other states also have voluntary based programs.)

In the recently passed New Jersey Commercial Organics Law, Senator Bob Smith, D-17th District, the bill’s main sponsor, argued that the legislation would create an entirely new industry, revolving around environmentally conscious food recycling, rather than letting it sit in a landfill where it would produce methane gas. In the years to follow, the booming industry would drive down costs and vastly outdo any expenses that businesses might incur in the near future, according to a report in njbiz.com.2 Previous versions of the bill had exceptions for landfills with landfill gas (LFG) beneficial-use facilities onsite, but that was pulled in the final version.

Issues and Challenges

Any discussion on the merits of the organics diversion must answer a few important questions:

• Is it realistic to build new facilities that handle organics when we already have existing solid waste facilities that are equipped to handle the material?

• If we remove organics from the waste stream, what existing infrastructure needs to be duplicated if an organics management facility is designed to handle these materials?

• Is there a significant impact to LFG generation if we remove the commercial portion of the organics from the waste stream at a landfill?

Impact of Removing LFG

One of the most important challenges is the impact on LFG generation if organics is removed from the landfill. Removing organics may get two to three years more site life, but we will get less LFG annually. Depending on the LFG delivery contract, 200 to 300 standard cubic feet per minute (scfm) might be the difference between a facility making its numbers and going into default on its contract.

One of the most important challenges is the impact on LFG generation if organics is removed from the landfill. Removing organics may get two to three years more site life, but we will get less LFG annually. Depending on the LFG delivery contract, 200 to 300 standard cubic feet per minute (scfm) might be the difference between a facility making its numbers and going into default on its contract.

When one begins to implement an organics diversion program, it takes time to build up programs and transition over to diversion, so there is still the opportunity to recover the gas in landfills until organics diversion takes place and the participation level grows over time. These windows to get renewable products to market should be factored into the calculations.

When one begins to implement an organics diversion program, it takes time to build up programs and transition over to diversion, so there is still the opportunity to recover the gas in landfills until organics diversion takes place and the participation level grows over time. These windows to get renewable products to market should be factored into the calculations.

Permitting

Permitting of these facilities takes time. Irrespective of its environmental benefits, neighbors may not consider food waste facilities to be the best neighbors.

Permitting of these facilities takes time. Irrespective of its environmental benefits, neighbors may not consider food waste facilities to be the best neighbors.

Building trust by communicating with residents and regulators about how you will operate, using best management practices, odor control, and following a facilities operation manual will gain trust. Working to build relations with the community will result in people thinking of the facility as a public utility focused on the creation of renewable products.

Building trust by communicating with residents and regulators about how you will operate, using best management practices, odor control, and following a facilities operation manual will gain trust. Working to build relations with the community will result in people thinking of the facility as a public utility focused on the creation of renewable products.

Communication and education are going to manage some of these NIMBY issues that crop up during permitting. For example, in Massachusetts, there is a voluntary interest and growing demand to source separate, close the loop and bring compost back into the community. People like it and like being part of it.

Revenue and Costs

We have already discussed the loss of LFG—if you take enough organics out of the waste stream it is going to be tough for owners to make up the difference. The national estimate is that food waste is 22 percent of MSW disposed in landfill. If you estimate that 30 percent of the waste stream will be affected by diversion legislation, that is about 7 percent of the total waste stream, which could be a major impact to gate receipts, capital budgets, as well as LFG production.

We have already discussed the loss of LFG—if you take enough organics out of the waste stream it is going to be tough for owners to make up the difference. The national estimate is that food waste is 22 percent of MSW disposed in landfill. If you estimate that 30 percent of the waste stream will be affected by diversion legislation, that is about 7 percent of the total waste stream, which could be a major impact to gate receipts, capital budgets, as well as LFG production.

It may extend site life by a couple of years, but at a tipping rate of $100 per ton we are looking at a revenue drop of $3.5 million per year for a site that loses 35,000 tons per year of intake; at tipping fees of $50 to $60 per ton, that is still $1.5 million a year not coming across the scale. In addition, overall costs are far higher. There are more facilities, trucks, labor costs and fuel usage; more trucks burning more diesel is the antithesis of what we are trying to accomplish. We must pay attention to these hidden costs.

New technology is being developed to address these issues, providing innovation and cost effective and sustainable programs that can be built out and scaled up over time. What we need is equipment for processing/monitoring to generate data to help determine what kind of project would best serve a particular area. It might be organics to AD for some and composting for others.

New technology is being developed to address these issues, providing innovation and cost effective and sustainable programs that can be built out and scaled up over time. What we need is equipment for processing/monitoring to generate data to help determine what kind of project would best serve a particular area. It might be organics to AD for some and composting for others.

Take the example of the Organix Co-Collection™ program implemented in Minnesota, where residents source separate food scraps into a specific compostable bag designed for co-collection. The compostable bag goes in the same cart with the trash and is picked up by the hauler on the regular collection route. Compostable bags are separated at a transfer station or waste facility and delivered to a commercial composting facility. No additional carts, routes or trucks are needed, and this collection method reduces GHG emissions and road wear. Cost effective and sustainable, this approach reduces costs for organics collection. It might be applicable for a variety of commercial/institutions, such as schools, hospitals and corporations.

Infrastructure

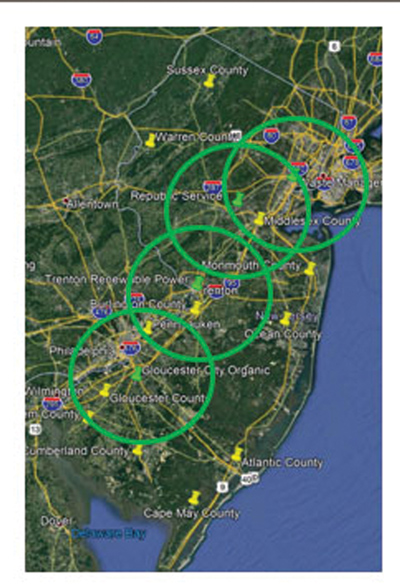

Let’s look at the infrastructure issue through the lens of the New Jersey case, shown on the accompanying map (see Figure 3). There are 12 active MSW landfills (yellow pins) and four approved organic recycling locations (green pins); the green circles indicate a 25-mile road distance radius. Generators can apply for a waiver if recycling cost is >110 percent of current disposal cost. The legislation affects the service area of at least nine of the 12 active NJ landfills.

Let’s look at the infrastructure issue through the lens of the New Jersey case, shown on the accompanying map (see Figure 3). There are 12 active MSW landfills (yellow pins) and four approved organic recycling locations (green pins); the green circles indicate a 25-mile road distance radius. Generators can apply for a waiver if recycling cost is >110 percent of current disposal cost. The legislation affects the service area of at least nine of the 12 active NJ landfills.

Under this legislation, large commercial generators would need to source separate—with potentially three sets of pickups every week (MSW, recycling and food waste). New facilities would be required for those not near the approved recycling locations, requiring new infrastructure, roadways, scales and power distribution. More labor would be needed for de-packaging (and disposing of the packaging) and there could be significantly more truck traffic.

It might be quite difficult for an existing facility to develop a new organics recycling component due to space issues. For example, a 100 ton per day (TPD) composting facility layout requires 10 to 15 acres, while a wet AD layout for 100 TPD requires 2 to 4 acres, and a dry AD layout for 100 TPD needs 5 to 7 acres. A lot of sites simply do not have this much space. And will it even pay to do so? Capital expenses for an AD system handling 100 TPD of food waste would be about $25 to $35 million, with $1 to $1.5 million in annual operating expense. That is a cost of $75 million for 20 years. At a $50/ton tipping fee, the operator would earn about $1.4 million per year. This is only $38 million in revenue—meaning only half the costs would be recovered.

There is another way of looking at this. We must look at the great opportunity for management of up to 30 percent of the solid waste stream. We should be looking at ways to build organics recycling within or alongside existing solid waste infrastructure.

There is another way of looking at this. We must look at the great opportunity for management of up to 30 percent of the solid waste stream. We should be looking at ways to build organics recycling within or alongside existing solid waste infrastructure.

This could be an opportunity for municipalities—they could reduce hauling time and still keep their hands-on tonnage they would otherwise lose. The facilities represented by yellow pushpins located outside of the 25-mile radius shown on the map should ask themselves, “What can I do to still hold on to organics tonnage?” There is an opportunity to look at building regional or even community-based composting facilities. An existing transfer station might be able to play a role in collecting and transloading to a regional structure.

Here is How to Make it Work: AD Combined With Vehicle Fuel Makes Money

We know legislation is forcing the discussion of organics recycling in many states. We also know that there is duplicate infrastructure needed for a standalone organics recycling facility and we know there are real concerns about the economics—what could a facility look like that addresses these items?

We know legislation is forcing the discussion of organics recycling in many states. We also know that there is duplicate infrastructure needed for a standalone organics recycling facility and we know there are real concerns about the economics—what could a facility look like that addresses these items?

If a landfill owner sets up their own AD or composting operation, they could keep the food waste intake/revenue that they have now and potentially open new markets. To do so, they would need to account for odors (different odors but odors nonetheless): waste liquids, equipment and truck traffic, and de-packaging costs. Here is one way it could work—combining AD with producing vehicle fuel at an existing solid waste management facility.

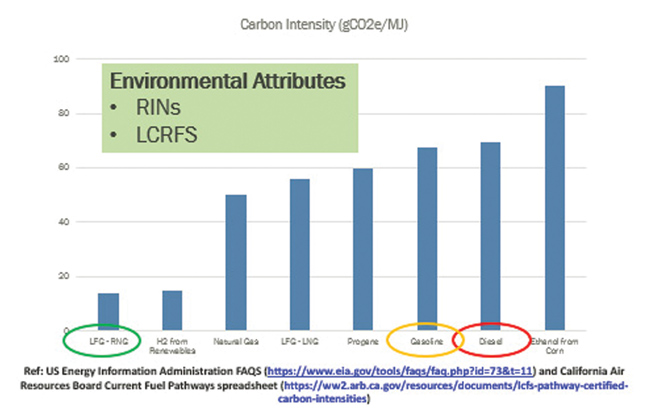

Earlier, we reviewed the figures for a 100 TPD AD food waste system. Now let’s add 350 to 400 scfm of biogas @ 70 percent CH4 and 0 percent O2, which could be cleaned up and injected into a pipeline as a renewable natural gas (RNG) or converted to C-RNG and used as a green, very low-carbon intensity vehicle fuel. Effluent (waste liquids) would be discharged to a WWTP or solidified and landfilled. Residuals would be landfilled (see Figure 4).

Graphic compiled by Tetra Tech.

In this example, 400 scfm of biogas can produce about 650,000 diesel gallons equivalent (DGE) per year. The initial capital cost would be about $3 to $5 million. The O&M costs to produce the RNG are about $1/DGE or approximately $650,000/year. Subtract the diesel you are not buying @ $2.50/gallon ($1.63 million/year) and RNG incentives (RINs) @ $2.40/DGE of $1.56 million/year. This leaves you about $23 million in costs over 20 years and $85 million in revenue. Combining RNG and AD, you could incur $98 million in costs versus $123 million in revenue over that 20-year period. Another alternative would be to forego fuel production and inject the RNG into a pipeline with a delivery contract in California so you can generate Low-Carbon Fuel credits.

AD combined with vehicle fuel makes money over the long haul. It also introduces the desirable circular economic opportunity discussed earlier. In addition, solid waste facilities are already designed to address traffic, odors, biogas and leachate. Co-location eliminates the duplication of certain infrastructure costs (since the infrastructure exists). In fact, if it is deemed to be a green project, it might even be easier to permit. Such a facility may maintain and increase the revenue stream and, with upcoming technology, prevent the need for separate haul pick-ups at the curb.

And let us not forget the other environmental benefits organics recycling brings, even though they may be hard to tally. These include bringing back healthy soils. If we start to use composted food waste and replace chemical fertilizers, we will be building healthier communities and making the water healthier too.

To make the world safer and healthier, it makes a lot of sense to recycle organics. One approach that deserves consideration is a move towards landfills accepting organics processing through AD. While we acknowledge the tensions of our different perspectives, we both agree that creative persistence can find workable middle ground.

Thomas Bilgri, P.E., is the Manager of Biogas Engineering Services for Tetra Tech (Pasadena, CA), with more than 30 years of LFG management system design, engineering and permitting experience. Thomas has conducted numerous assessments of LFG production for existing and proposed landfill facilities throughout the world and has provided onsite assessments of surficial and subsurface LFG migration and the evaluation and response to odors related to landfills and LFG systems. He has also been engaged in the development of beneficial-use projects, including direct sale, electrical generation, compressed natural gas (CNG), liquefied natural gas (LNG) and high-BTU gas production facilities. He also serves as the Chairman of the SWANA LFG/Biogas Technical Division Program Committee. Thomas can be reached at [email protected].

Debra Darby serves as Manager, Organics Sustainability Solution, for Tetra Tech. She is involved with consulting, compliance, permitting and developing the operations of organic materials management systems. She also works in solid waste planning, assisting clients to reach their sustainability and zero waste goals through the design and implementation of organics recycling programs and technologies, including composting and anaerobic digestion. Debra can be reached at [email protected].

Notes

1. In this context, organics management includes collection, processing, treatment and re-use of organic material, including green waste, food waste, biosolids, farm and dairy waste, and forestry materials.

2. https://njbiz.com/murphy-signs-bill-boost-food-waste-recycling-new-jersey