The demise of local recycling with the implementation of EPR programs may be overstated. The real issue is to develop EPR programs that balance the needs of all the stakeholders in the overall recycling program to improve success.

Marc J. Rogoff, Ph.D.

In recent years, procurers and manufacturers have developed a great many industry programs to help reduce the lifecycle impacts of various consumer products and packaging. There also has been a movement by local governments, states and provinces in North America to help shift the responsibility from taxpayers and ratepayers to these producers. Not surprisingly, the merits of this movement have been hotly debated in some quarters, particularly in light of the current recycling infrastructure investments already made by local governments. The terms “extended producer responsibility” and “product stewardship” are also bandied about with little, if any, agreement by many of what these terms actually mean. This article will attempt to provide some guidance on this subject for those of us involved in solid waste management.

What is Product Stewardship?

Product stewardship is oftentimes defined as the act of restructuring the way manufacturers design and market products so that they optimize recycling of materials, minimize packaging, and actually design their products in a way that will enable complete recycling of the used product in lieu of disposing the used product. It is essentially a “cradle to cradle” strategy instead of a “cradle to grave” approach.

The Product Stewardship Institute (PSI) is a U.S., non-profit membership-based organization, located in Boston. PSI works with state and local government agencies to partner with manufacturers, retailers, environmental groups, federal agencies and other key stakeholders to reduce the health and environmental impacts of consumer products. PSI takes a unique product stewardship approach to solving waste management problems by encouraging product design changes and mediating stakeholder dialogues. Several states have or are considering initiatives and laws that would encourage or require manufacturers to improve their product designs in this manner.

Economic prosperity has increased per capita spending over the past several years and increased the need for local governments to provide expanded recycling and disposal programs. Product stewardship is a concept designed to alleviate the burden on local governments of end-of-life product management. Product stewardship is a product-centered approach that emphasizes a shared responsibility for reducing the environmental impacts of products. This approach calls on the various waste generators to help minimize their wastes:

- Manufacturers: To reduce use of toxic substances, to design for durability, reuse and recyclability, and to take increasing responsibility for the end-of-life management of products they produce.

- Retailers: To use product providers who offer greater environmental performance, to educate consumers on environmentally preferable products and to enable consumers to return products for recycling.

- Consumers: To make responsible buying choices that consider environmental impacts, to purchase and use products efficiently, and to recycle the products they no longer need.

- Government: To launch cooperative efforts with industry, to use market leverage through purchasing programs for development of products with stronger environmental attributes and to develop product stewardship legislation for selected products.

The principles of product stewardship recommend that a role of government is to provide leadership in promoting the practices of product stewardship through procurement and market development. Environmentally Preferable Purchasing (EPP) is a practice that can be used to fulfill this role. EPP involves purchasing products or services that have reduced negative effects on human health and the environment when compared with competing products or services that serve the same purpose. They include products that have recycled content, reduce waste, use less energy, are less toxic and are more durable.

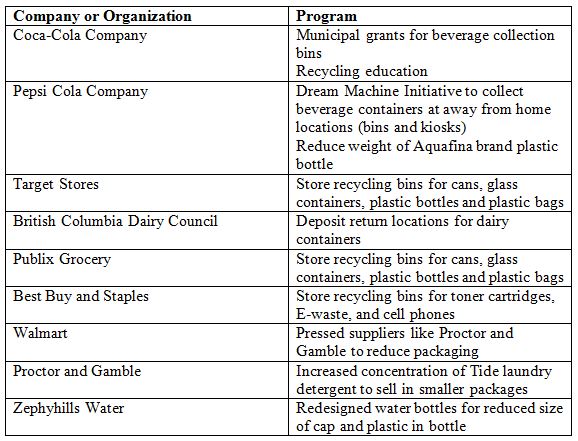

Table 1 provides details on a few examples of programs undertaken by North American producers of consumer packaged goods. Local, state and federal government agencies can and do use their tremendous purchasing power to influence the products that manufacturers bring to the marketplace. In the last decade or so, most efforts have focused on encouraging procurement of products made from recycled content. The goal of these procurement programs is to create viable, long-term markets for recovered materials. The EPA has developed a list of designated products and associated recycled content recommendations for federal agencies to use when making purchases. These are known as Comprehensive Procurement Guidelines.

To date, EPA has developed more than 60 guidelines that fall into the general categories of construction products, landscaping products, non-paper office products, paper and paper products, park and recreation products, transportation products, vehicular products and miscellaneous products. For example, federal agencies are instructed to buy printing or writing paper that contains at least 30 percent post-consumer recycled content.

What is Extended Producer Responsibility?

In recent years, extended producer responsibility (EPR) has emerged as a general policy approach which aims to shift the cost of managing consumer packaging from local solid waste agencies to those manufacturers who are producing these products. As its name implies, EPR extends the role of manufacturers to include the recovery and recycling of materials and financial responsibility for public operating expenses. Those promoting EPR asset four major advantages for EPR as a preferred policy approach for end-of-life management for packaging and printed paper:

- EPR causes producers to change packaging design and selection, leading to increased recyclability and/or less packaging use

- EPR provides additional funds for recycling programs, resulting in higher recycling rates

- EPR improves recycling program efficiency, leading to less cost, which provides a benefit to society

- EPR results in a fairer system of waste management in which individual consumers pay the cost of their own consumption, rather than general taxpayers

In the U.S., more than 70 producer responsibility laws have been promulgated in 32 states including 10 categories of consumer products such as: automobile batteries, mobile phones, paint, pesticide containers, carpet, electronics, thermostats and fluorescent lamps. In recent years, there has been a rising tide of states, which have passed E-waste EPRs as a consequence of the rapid replacement of these products. Several states have enacted landfill bans, which have had an increasing positive impact of product recycling. However, as of this date, no state has enacted an EPR law of programs extending to packaging or printed paper.

As a result of failed voluntary packaging take back programs in the Europe; public policies were instituted to require manufacturers to be responsible for these materials. In 1994, the EU enacted the Packaging Waste Directive (94/62/EC) requiring its member states to develop regulations on the prevention, reuse and recycling of packaging waste. These regulations vary from country to country, but most counties mandate that manufacturers pay some of all of the costs of packaging collection and recycling in the form of producer financing, shared costs, tradable credits or packaging taxes. Many countries in Northern Europe (Austria and German) have decided to develop collection programs for packaging completely separate from solid waste. Shared systems, which split or share municipal authority with manufacturers, are typical of programs existing in Southern Europe.

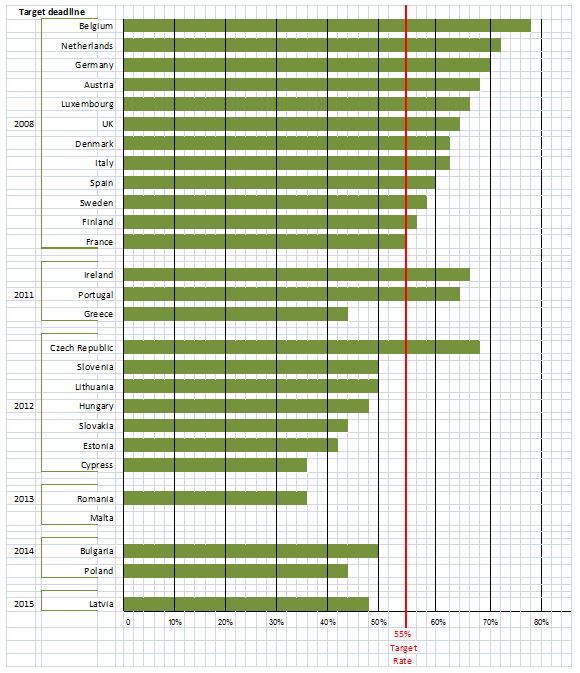

Figure 1 shows packaging recycling rates in European countries as of 2009. The data show that 17 countries target of the Packaging Waste Directive (2004/12/EC) to recycle at least 55 percent of packaging waste generated, and two countries missed the 2001 target to recycle at least 25 percent. The highest performing programs in recent years include Denmark (84 percent), Belgium (79 percent), Netherlands (72 percent), Germany (71 percent), and Austria (70 percent).

EPR in Canada

Canada’s commitment to EPR was formalized in the Canada-Wide Action Plan, which was promulgated in 2008. EPR legislation is in existence in all of Canada’s 10 provinces, with four (Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba and British Columbia) having major programs in place. These programs resulted from similar failures of voluntary take-back programs. Ontario and Quebec requires manufacturers to pay 50 percent of the program costs, Manitoba 80 percent and British Columbia 100 percent. In addition, all provinces have enacted deposit systems for beer containers, with eight provinces having similar deposit laws for soft drink containers.

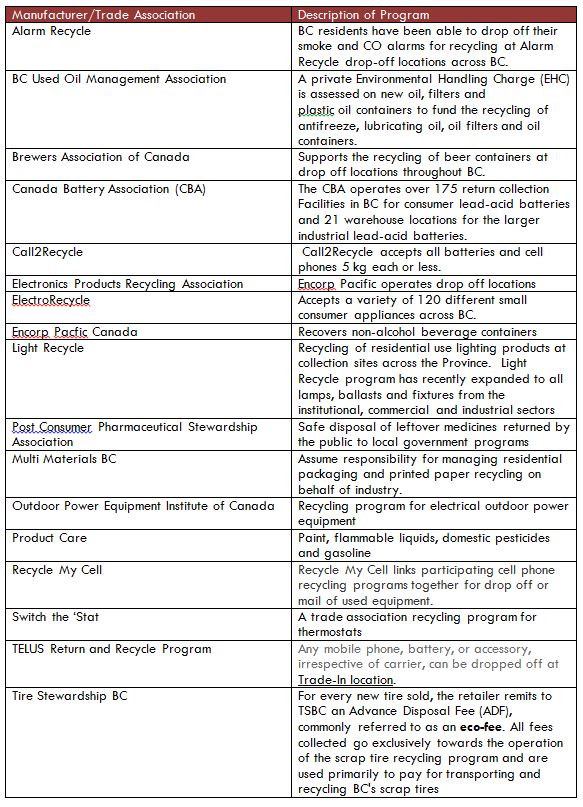

EPR in British Columbia has been the most comprehensive among all Canada’s provinces. In 1970, the Province enacted one of the oldest beverage container recovery systems in North America. More than 40 years later, this system has evolved into a collection, recovery and management system designed to deal with a variety of regulated products (see Table 2). These programs are managed by industry stewardship associations based on a stewardship plan submitted to and approved by the Ministry of the Environment.

Funding is either generated through advance disposal fees paid at point of retail or as part of the price of the product. The stewardship organizations track program activity, measure the results against the established objectives within their approved plan and then report those results annually to Ministry. Every five years the producer must review the approved plan and submit any amendments if applicable or advise the director in writing that the approved plan does not require changes.

Lessons Learned for the U.S.

While the EPR concept has also caught on in Europe, Canada, Latin America and Asia, it has until recently has been little more than a foreign buzzword in the U.S. In a recent review of the state EPR regulations and programs, Jennifer Nash and Christopher Bosso, professors at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University have noted the poor EPR performance across the U.S. Their review suggests that results to date in the U.S. in terms of pounds collected per capita are disappointing. For example, manufacturer-initiated collection programs for rechargeable batteries, mercury thermostats and mercury auto switches have reported low diversion rates. That is, about 10 to 12 percent for rechargeable batteries, less than 25 percent for mercury auto switches, less than 10 percent for mercury thermostats and about 15 to 20 percent for waste electronics. Further, high performance goals set out by states like Minnesota for rechargeable batteries (e.g., to recover 90 percent of designated battery types by 1995) have yet to be realized even a decade later. These results are very sobering to say the least.

Conclusions

Over the past three decades, local governments in the U.S. have invested literally hundreds of millions of dollars in developing the recycling infrastructure (e.g., curbside collection programs, drop-off stations, materials recovery facilities, etc.). This has been accomplished as a collaborative program among local governments, waste haulers, recycling markets and not-for-profit recyclers. Opponents of EPR fiercely argue that these “links” developed would be broken and be a fundamental shift in local community control. Recycling decisions would then be made by industry who would then control all aspects by producers whose sole interest is to manufacture products and not to provide recycling service. My research suggests that these predictions on the demise of local recycling with the implementation of EPR programs may be overstated somewhat. In my opinion, the real issue is to develop EPR programs that balance the needs of all the stakeholders in the overall recycling program to improve success.

Marc J. Rogoff, Ph.D. is a Project Director with SCS Engineers (Tampa, FL)

Marc Rogoff, PhD, is SCS Engineer’s National Partner on Solid Waste Rate Studies. He has more than 30 years of experience in solid waste management as a public agency manager and consultant, and has managed more than 200 consulting assignments across the U.S. on all facets of solid waste management, including waste collection studies, facility feasibility assessments, facility site selection, property acquisition, environmental permitting, operation plan development, solid waste facility benchmarking, ordinance development, solid waste plans, financial assessments, rate studies/audits, development of construction procurement documents, bid and RFP evaluation, contract negotiation and bond financings. Marc can be reached at (813) 621-0080 or via email at [email protected].

References

- EUROPEN, Packaging and Packaging Waste Statistics in Europe: 1998-2008, The European Organization for Packaging and the Environment, 2011.

- Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Does the Citizens Recycling Movement Face a Hostile Takeover? July 2013.

- King County, Washington, “Position Statement on Product Stewardship,” September 18, 2013.

- MacKerron, Conrad, Unfinished Business: The Case for Extended Producer Responsibility for Post-Consumer Packaging, As You Sow, 2012.

- Nash, Jennifer and Christopher Bosso “Extended Producer Responsibility in the United States: Full Speed Ahead?” Journal of Industrial Ecology, 17(2): 175-185, 2013.

- Rogoff, Marc, Solid Waste and Recycling and Processing, 2nd Edition, Waltham, MA, Elsevier/William Andrews, 2014.

- SAIC, Evaluation of Extended Producer Responsibility for Consumer Packaging, Produced for the Grocery Manufacturers Association, 2012.