Examining and deploying the elements of a formal asset management process is fundamentally necessary to make your business profitable and sustainable.

By John Ross

Increasing capital costs, the need for extended asset life, a dearth of technical skills in this country, and just plain ol’ economics has led many industries to a tipping point. Certainly, the waste and recycling industries are not far behind, but do you think it would be better if we were farther ahead?

Asset Management

In the U.S., the manufacturing world is beginning to take notice of the newest ISO standard from Europe, ISO 55000 or Asset Management. At its core, Asset Management is a strategic study of the lifecycle of an asset, or assets. A study, not in the traditional sense, but rather one that is meant to position the identified corporate assets to deliver value to the organization. As such, all organizational systems (operations, HR, safety, finance, engineering, maintenance, etc.) are calibrated to aim right down the barrel of ensuring that assets perform to expectation and deliver on their value promise.

Those with little knowledge of waste management, waste conversion, recycling, transfer stations or landfill operations will not intuitively consider that ours is an industry comprised of assets. Let’s face it, the population-at-large would rather assume those responsible for these businesses conduct their affairs out of sight and out of mind. Does a person stuck behind a garbage truck and already late for an important meeting view that truck as an asset? Probably not. Those of us in the industry know better and know that the assets of our industry are the very things that make the magic happen. To a larger extent, the assets of our companies actually ‘print’ the money that pay the paychecks.

What is an Asset?

I wrote ‘things’ in italics because not all assets are physical in nature. The wording used in ISO 55000 to describe what an asset is seems a bit wordy, yet it is comprehensive: “Any tangible or intangible item, thought, process, concept, or substance of value that can be manipulated for financial gain.” Like most businesses, ours requires a profit to keep the investment wheel spinning.

Before we can examine how assets can be manipulated for financial gain, it is vital to first determine exactly what an asset is. I like to shorten the ISO 55000 definition paraphrased above and simply adopt the definition of an asset from Robert Kiyosaki. He states that, “An asset makes income.” Can that be any easier to understand?

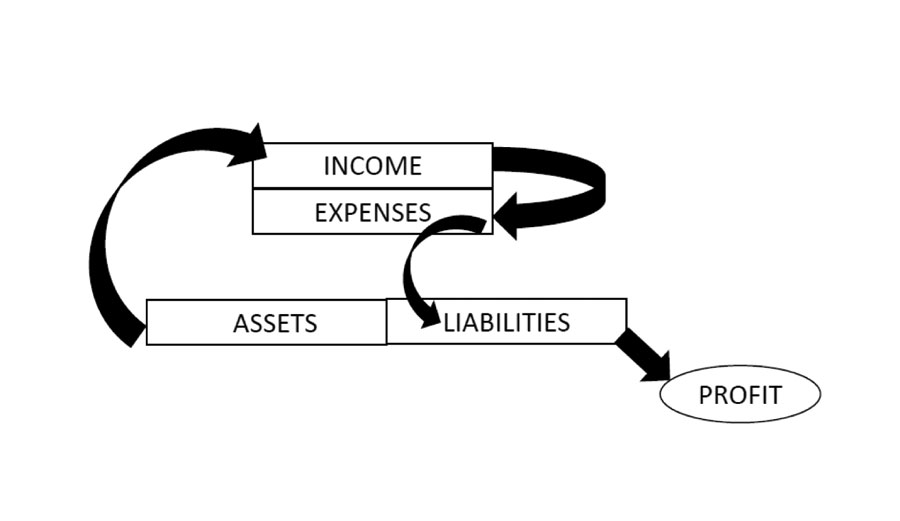

Kiyosaki graphically represents the relationship between assets-income-expenses-liabilities-and profits in his book Rich Dad, Poor Dad and clearly puts the value of assets in perspective. Figure 1 is an interpretation of Kiyosaki’s model.

The Figure 1 model indicates that assets make income. From that income, companies pay their expenses, then service their liabilities. The result is profit which is in turn reinvested back into the company to buy more assets. Common company assets might include, but are certainly not limited to:

• Human resource assets (people)

• Financial assets

• Property assets

• Trade secrets or proprietary assets

• Processes

• Inventory (the right inventory)

• Accounts receivable

• The company logo and name

• Physical assets (equipment)

Organizational Objectives

As a Certified (and practicing) Maintenance and Reliability Professional (CMRP), I am often concerned with the physical assets or rather, the equipment. Asset Management, or the practice as outlined by the dictates of ISO 55000, and quite honestly just common sense, tell us that our engagement with the company’s assets (physical and otherwise) has to be in concert with the corporation’s organizational objectives. Is anyone, or better yet, is everyone in your company aware of the organizational objectives? It is very likely that they are not. Several of the more common organizational objectives are:

• Profitability and cash flow

• Productivity (of people and resources)

• Customer service

• Core values

• Growth (sustainability)

• Change management

• Beating the competition

To recap so far, company assets make income. You are an asset, your friend at work is an asset, the equipment you use is an asset, and the name of your company is an asset. Assets make income. Organizational systems, and therefore, the people that operate within the systems, are charged with ensuring that the company assets are delivering value for the company. The entire operation should be churning along a continuum in line with the organizational objectives. Two of which are to be profitable and to be sustainable.

Keeping the Assets Operational

To be profitable, and presumably sustainable, a company must sell products or services for more than they cost to produce them. One can correctly assume, with just a hint of creative thinking, that capital intensive companies, like those engaged in the waste and recycling industries, must have physical equipment that operates reliably and with a great deal of availability. As stated earlier, “…the assets of our industry are the very things that make the magic happen.”

Until the advent of formal asset management, the manufacturing and service industries were left to seek out a means to put this ideology into an understandable context. What came from a careful study of the ISO standard’s requirements, coupled with globally recognized good practices, was a comprehensive means to ensure assets deliver their value, and that we maintain them at a price that guarantees profitability and sustainability. Manufacturing and service industries are just now learning these valuable lessons and capitalizing on the momentum of aligning everyone with the organizational objectives to ensure that assets make income. Part of ensuring that assets will return value is to take the necessary steps to allow the physical assets to be in a condition to actually work when needed. In fact, the very definition of reliability is that “equipment does what it is supposed to do, when it is supposed to do it, for as long as it is supposed to.” The contribution from the maintenance and reliability function is to keep the assets operational. To stay profitable and sustainable, this has to be accomplished pragmatically and with constant measure of ‘cost versus value.’

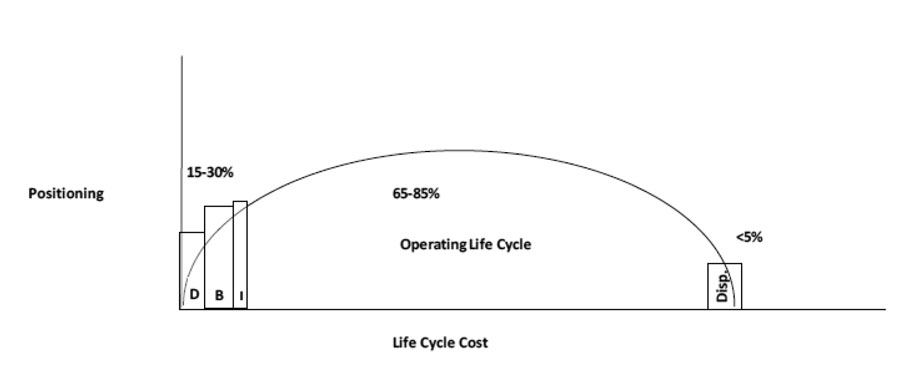

Let me explain by way of example. Ramesh Gulati, in his key work Maintenance and Reliability Best Practices, really lays some groundwork for our consideration. In his book, Gulati provides the idea of a Life Cycle Cost curve. I have recaptured his position in Figure 2.

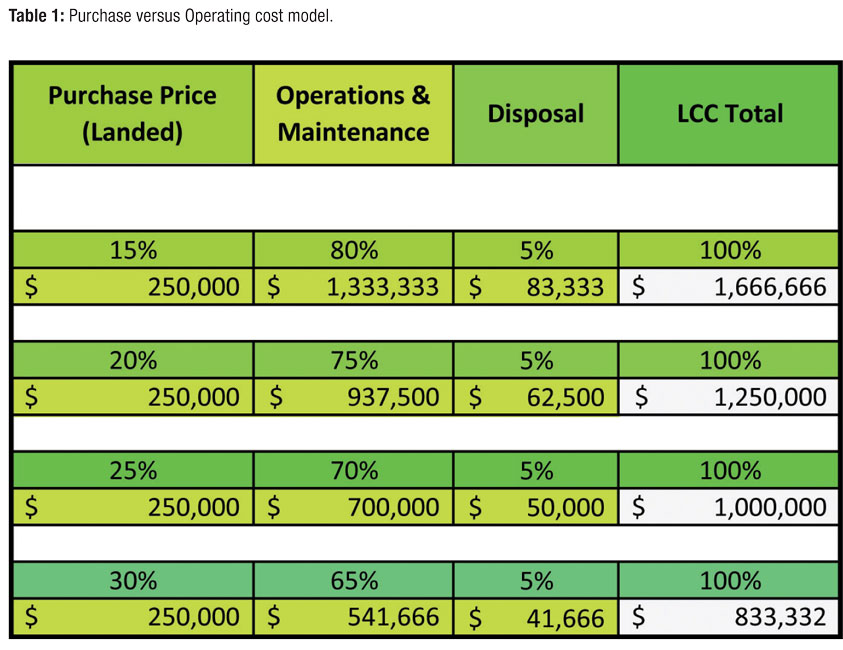

From this curve we can extrapolate different cost models along the ranges that Gulati provides. In our example scenario, we are going to purchase a new $250,000 garbage truck. This is the ‘landed’ price at our location, or DBI shown in Figure 1. Table 1, page 59, becomes the cost options we have to consider for this purchase. Not only are we arriving at a breakdown of purchase versus operating/maintenance costs for this purchase, but also if we think strategically, we can use this model for all capital equipment purchases. This delivers a great sense of cost predictability for our operating budgets.

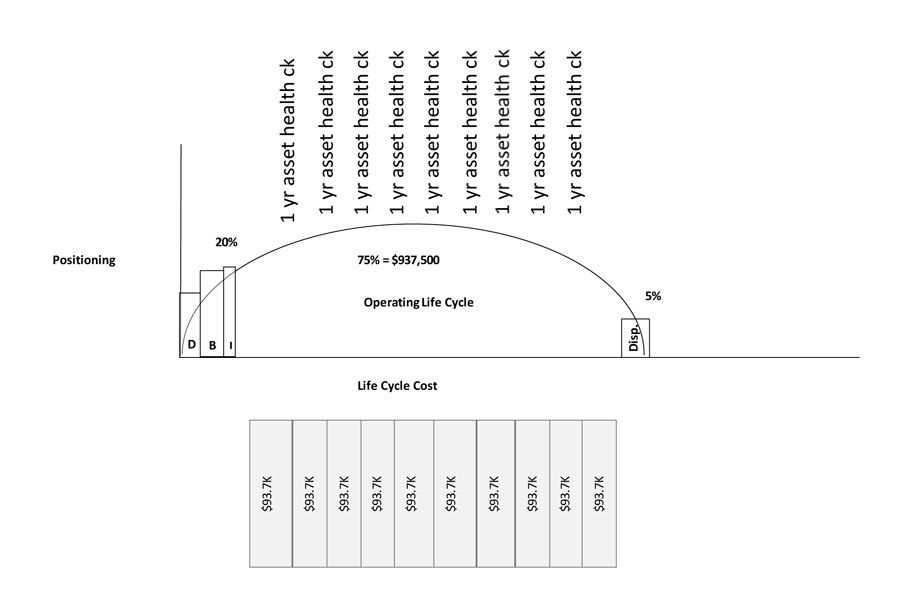

For our example purchase, our company has agreed that our strategic capital purchasing will be around the 20 percent purchase price model shown in Table 1. Using this table, at this percentage point, communicates that our intention is to spend approximately 75 percent of the lifecycle cost, or in this case $937,500 over the depreciated life of the asset—the garbage truck. Calculating a 5 percent cost for disposal nets us a total lifecycle cost for that truck of $1,250,000. So what, right?

If we use a 10-year depreciation position, we now know that our intentions are to spend no more than $93,750 a year on operating and maintenance expenses (not including fluids). This information is of great strategic significance if you are trying to be profitable and sustainable.

Asset management standards require that all company stakeholders execute their responsibilities to ensure that the asset provides continued value to the company. Our charge in the maintenance and reliability fields becomes one in which we adapt to a philosophy that delivers on that mandate. ISO 55000 calls these maintenance actions ‘control activities,’ but they are simply the usual planning and scheduling, preventive and predictive maintenance, good storeroom control, and sound maintenance practices.

Total Productive Maintenance

Fortunately for those seeking to really get a handle on sustainability (also meaning profitability) and some control of their operating budgets, the globe’s number one reliability methodology has been in the U.S. since the 1980s. Also developed overseas (with great influence by American George Smith), Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) is the cornerstone for every single advancement in maintenance and reliability in the world. TPM as a practice, was greatly enhanced in the 1990s and is now a more robust approach known as Total Process Reliability, or TPR. TPM was bolstered with some missing elements to morph into TPR, most notably, Root Cause Analysis and Early Equipment Design or Design Excellence.

In the end analysis of our fictional purchase, if we have hopes of maintaining a level of operations and maintenance expenditures around the $93K-a-year mark, we need an enhanced, formal, and structured approach to the asset upkeep and reliability such at TPR. Rounding out our execution of the tenants of Asset Management, I suggest an annual asset health review to determine if the asset is still returning value to the company and if the projected engagement of the asset is possible given its condition at the time. That process might look something like Figure 3.

By adapting an ‘everyone is responsible for the asset’s performance and value’ theology to the execution of our corporate policy, we can better engage associates (who are also assets) by them having a role in protecting and caring for the very equipment that metaphorically prints their paychecks. Talk about a morale booster.

Stitching it All Together

Examining and deploying the elements of a formal asset management process is fundamentally necessary to make your business, profitable and sustainable. Deployment of Total Process Reliability is the practice professional organizations use to stitch this all together.

The only question left to ask in this study of profitability and sustainability is, “are you far behind or far ahead?” | WA

John Ross, PhD, CMRP is a senior consultant with the Raleigh, NC-based, international maintenance and reliability consulting company, TBR Strategies. John has been professionally engaged with reliability efforts for more than three decades and continues to spread a positive message globally. He is a former Captain in the United States Air Force, serving as an Aircraft Maintenance Officer. John is a Gulf War veteran. In addition to his consulting work, John is a prolific author and public speaker. He has penned more than a dozen maintenance and reliability publications, and is the author of two best-selling books on the subject: The Reliability Excellence Workbook, From Ideas to Action, and Cover Your A$$ets, Asset Management at Your Place and at Your Pace. John has presented at the annual Society for Maintenance and Reliability Professionals (SMRP) annual conferences and has been the key note speaker at several maintenance and reliability forums. He is the primary instructor for North Carolina State University’s diploma series for Maintenance and Reliability Management (MRM). John holds an AS, BS, MS, and PhD as well as a U.S. Patent. He can be reached at [email protected].