Roadkill rarely challenges a landfill operator. However, when the USDA calls looking for somewhere to dispose of 5 million chickens felled by bird flu, a plan is good to have.

By Michael Cook, PE

Accepting dead animals is nothing new for a landfill. When the county roads department scoops up and drops off road kill, no one thinks twice—unless you are within smelling range. A local farm may have to put down a few head of livestock for some reason, and those animals may end up in the landfill. Livestock may die in a massive weather event, as thousands of cattle and other animals did in October 2013 when an early winter storm dropped more than a foot of snow in western South Dakota, stranding and freezing animals in fields and pastures. And while many farms, fortunately, had enough room to bury those carcasses on their own land, the situation soon spurred questions about what roles waste disposal facilities—landfills—might play should another mass animal emergency occur.

Harsh reality struck just two years later. In 2015, dozens of farms in the central U.S. were affected by an outbreak of the H5N2 virus, a variant of the avian influenza considered highly pathogenic and resulting in high mortality. Once commercial poultry operations are infected—typically by migratory waterfowl—containment becomes the priority. Many farms have several birdhouses and preventing the disease’s spread from one house to the next may require depopulating all animals in an affected house. If the flu spreads to the next house, the challenge is to prevent it from leaving the farm. In these cases, thousands to millions of birds are killed, either by the disease or through depopulation.

During the 2015 outbreak, 21 states were affected to some degree, with Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Missouri and Arkansas being most affected—more than 42 million chickens and 7.5 million turkeys are estimated to have died during the outbreak. Preventing an outbreak, or preventing one from spreading even farther, requires planning and options.

In this particular outbreak, more than 5 million of the affected chickens came from a single farm in northwestern Iowa. And while resulting losses were devastating for the single farm, preventing the flu’s spread was the paramount concern. Efficiently and effectively managing the outbreak required quick response and options for managing disposal. Area and regional landfills were approached about their willingness to assist with disposal and management of carcasses and all associated waste products (manure, bedding, eggs and other debris). Among those approached was the City of Sioux Falls Regional Sanitary Landfill (SFRSL), which, after assessing its options, opted against accepting the waste. The farm ended up managing the majority of its waste onsite, using compost windrows stretching for more than six miles. Elsewhere in Iowa, another affected farm was able to dispose its waste at a different Iowa landfill. In its aftermath, the event had uncovered two clear conclusions:

Disposal facilities in areas with the potential to be affected by a mass animal outbreak or health emergency should consider being a viable disposal option should the need arise.

Each facility should develop a plan that could be used to successfully manage safe, environmentally protective disposal.

The Questions

Managing animal carcasses can be handled in a variety of ways onsite, including burial, composting and incineration. In the event of a disease outbreak—where quick and environmentally safe management and disposal is paramount—landfills offer an excellent option because they generally have the space, personnel and environmental protections readily available (provided a plan is in place, that is). Landfills in areas at risk of mass animal health emergencies are likely aware of their industries and farms that have significant livestock populations. From a landfill’s perspective, accepting a large quantity of waste offers a potential revenue source that could offset the expected loss of airspace. Having a plan in place could reduce potential headaches, and help the disposal facility make the final call on whether to accept such waste.

Most landfills are permitted to accept animal carcasses—typically routine road kill that require no additional precautions or operational considerations. But during a mass animal health emergency, expect state and federal departments of agriculture and transportation to be among agencies involved. State and USDA officials generally take responsibility for managing an outbreak and provide the best possible resources for managing and handling such waste. To be effective, landfills should consider developing their own plans by engaging state and USDA officials along with farms that would be considered at risk during an outbreak. During an event, and should the landfill be a viable option, all parties involved would be ready to work together to provide the most effective and environmentally safe means of waste management.

The Plan

Having a plan in place enables rapid mobilization of necessary resources to manage the pending mass volume of waste. An event timeline may begin something like this:

- Farmer notices a series of unusual deaths of his hens.

- Farmer contacts the state department of agriculture, which opens an investigation.

- Cause of death is determined and potential threat is assessed.

- Remaining hens are depopulated to prevent an outbreak.

It is during this period—sometimes within 24 hours—that the need for managing or disposing of the waste effectively, efficiently and safely is determined. If landfilling is among the options, involving the appropriate city or county personnel and emergency management officials comes first. Next is mobilizing the resources necessary to handle and manage the actual waste.

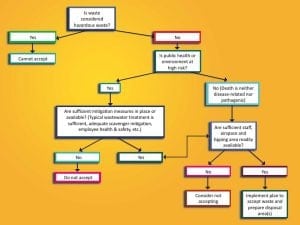

A “decision matrix” can help a landfill determine whether it can or should accept the waste. The matrix poses series of questions to help guide decisions (see Figure 1). The matrix solicits and accommodates input from all parties involved as decisions are made.

As a landfill manager or operator, engaging local farms ahead of an event like this helps reduce response times and answer questions as they arise. Such engagement should include creating a file with basic details: contact information for all potential parties involved, types of farms and livestock they have, animal volumes and/or quantities, etc.

A hauling route plan can prevent confusion, particularly if the potential exists for an outbreak to spread to other area farms. While waste haulers ultimately are responsible for complying with state and federal transportation requirements, landfill operators may want to require haulers to use leak proof containers—therefore preventing liquid waste from spreading potential contaminants. In establishing a haul route or routes, consider the need for alternative access into the landfill. Be sure to determine whether waste will be accepted after hours, as once hauling begins it is likely to continue nonstop until completion because affected farms need to dispose of their waste quickly. Require haulers to maintain a waste manifest at all times.

Even with preplanning efforts in place, an actual event often uncovers another inevitable challenge: mitigating public fear and perception. A local ordinance or policy may require that the public be notified when an area landfill will be accepting tens of thousands of dead chickens. In the event of a widespread outbreak, local or national media may already be providing enough information to make people aware of the events in their area. If a landfill neighbor or other concerned citizen discovers that the landfill is going to be accepting diseased animals, there may be negative public perception. It may be helpful to proactively demonstrate what the landfill is doing. Providing information about how the waste is going to be managed safely and handled in an environmentally responsible way to help stop the spread of the disease will go a long way to mitigating potential public concerns. USDA has resources available to help.

The Place

Determining where and how to dispose of such animal waste depends on the event. Protection of landfill staff, the public and environment is paramount. Waste from smaller events, such as a few thousand bird carcasses, may be easily mixed in with normal operations while still following special burial requirements. Determining what to do with 100,000 or 1 million bird carcasses may more challenging because the waste also includes manure, feed, eggs, bedding, waste from the cleanup and more. A trench 100 feet long, 10 feet wide and 5 feet deep is approximately 185 cubic yards; 100,000 chickens easily could consume more than 2,000 cubic yards of airspace.

Once the scope of incoming waste is identified, the location for disposal is determined. This should be within the waste disposal area footprint—that is, over a Subtitle D liner and leachate collection system. Assuming the waste cannot be managed at the typical working face, development of additional access roads and a dedicated area for tipping and staging may be necessary. Disposal trenches should be prepared and the area secured—unwanted customer traffic, storm water and nuisance animals should be kept out. In South Dakota, the state rules for solid waste require that a minimum of 6 inches of soil cover animal remains within 24 hours.

However, the South Dakota Animal Industry Board requires burial depth of at least 4 feet within 24 hours, so it can be assumed that this is the rule to follow, at least in South Dakota. State regulatory agencies’ waste programs may defer to certain state department of agriculture disposal requirements and this requirement should be verified within the plan. Another consideration would be placing an alternative daily cover over the waste between loads, to further mitigate potential environmental concerns.

Understanding the event’s scope helps determine equipment and personnel needs. The animal waste management plan should outline necessary equipment (e.g., an excavator) and staffing (e.g., overtime and scale attendant). It will also outline equipment necessary for cleaning and disinfecting stations; the need for staging cover soils ahead of time; and materials necessary for building access roads. USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) or state departments of agriculture will be actively involved in assisting the landfill with establishing cleaning stations and identifying routes and methods for disposal. Essentially, the landfill is responsible for providing a place to dispose the waste and providing personnel to operate disposal equipment. An additional consideration is that the landfill may contract third-party equipment and operators, and be only responsible for the scale.

APHIS and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide guidance literature regarding personal protective equipment (PPE) and waste handling. Protecting the health and safety of people managing and handling waste is critical. At a minimum, PPE should include: nitrile gloves, Tyvek coveralls, safety glasses, NIOSH 95 respirators and equipment cabin filters with equivalent NIOSH 95 ratings. Landfill personnel also should take precautions to mitigate storm water runoff and run-on, and airborne hazards. Waste disposal activities also should be properly documented, including surveying waste locations.

The Cost

When animal waste disposal can be managed concurrently with normal operations, there should not be any additional costs. In cases when additional equipment, staff overtime and other excess resources are necessary, additional costs to the landfill are likely. The potential impact on landfill airspace also should be considered. Among items that can lead to increased costs:

- Staffing

- Operators

- Scale attendant

- Oversight—someone may be required to document activities for federal reimbursement

- Equipment

- Earthmoving

- Wash stations

- Area preparation

- Site security

- Insurance/liability

- Loss of airspace

Here are ways to recover additional costs incurred during an event declared as a federal disaster or emergency:

- Become a federal contractor by registering with the federal System for Award Management (SAM) via www.sam.gov. Once registered, the landfill may:

- Contract directly with USDA to cover any additional costs. The landfill would be responsible for submitting all necessary paperwork for cost recovery.

- Contract with the affected farm under SAM. This also would require the landfill to provide documentation and information regarding costs associated with waste disposal, but would require the farm to recover the costs.

- Negotiate directly with the affected farm to establish a specific tipping fee for acceptance. This is essentially the same as contracting with the farm, but would not require registering with SAM. However, the farm would still require documentation for the costs.

The Decisions

Today’s modern landfills provide a viable means of disposal during a mass animal health emergency. Developing a plan and series of resources is critical in acting quickly to help prevent the spread of an outbreak affecting local residents’ livelihoods and economy. Engaging area farms that are potentially at risk is a first step in the teamwork and collaboration required to successfully manage such an event. Landfill operators should assess their facilities’ capabilities and limitations, and consider their desires for dealing with this kind of waste. If the facility is able and willing to manage such waste, a plan of operation should be developed—because an event is likely a matter of when, not if.

Michael Cook is a senior civil engineer at Burns & McDonnell (Kansas City, MO), where he works out of the firm’s office in Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN, and consults with municipalities, counties and commercial operators on landfill planning, permitting, construction, maintenance and operations. He can be reached at [email protected].