Just as you’re planning airline or automobile travel it’s always a good idea to “map out” your rail shipments so you have a good idea of the route to be traveled and an expectation of the time it takes to get from an origin to a destination.

Darell Luther

We spend a good deal of time working with customers that are new to rail and new to understanding the rail network, in particular where it goes and how it operates. We find that a general level of understanding of the rail system is very beneficial to rail shippers on several fronts. Understanding basic rail networks and their operations helps a company determine cycle times of their shipments, e.g. how long it takes for a loaded railcar to get from a particular origin to a particular destination and return of that railcar for loading; helps them plan their supply chain processes more accurately; and helps resource planning (human, machine and financial) on both ends of the spectrum, production, stockpiling or processing and loading at the origin and unloading, warehousing, stockpiling, processing, landfilling or recycling at the destination.

Rail Networks – Mapped

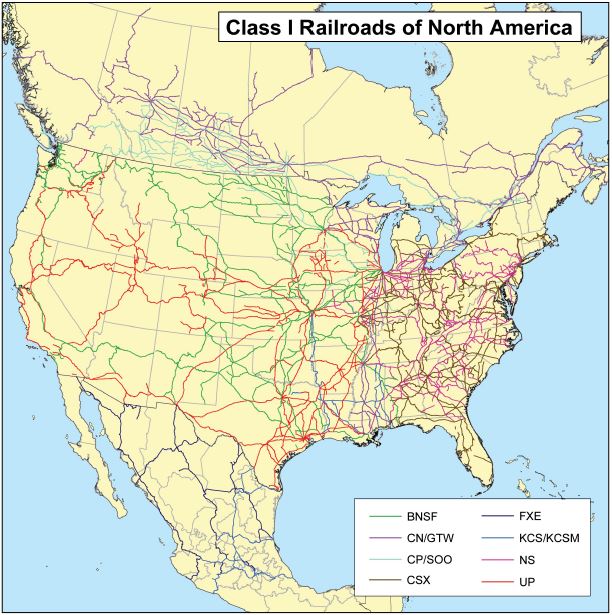

A great resource to start with on understanding rail networks is to look at rail maps that encompass the geographic area you intend to ship. Rail networks are comprised of seven Class I railroads, five in the United States and two in Canada, and over 500 shortline and regional railroads. As point of clarification a Class I railroad is one that has line haul revenue of $452.7 million (2012 basis). A regional and or a shortline railroad by definition have less than this amount in line haul revenue. A simply way to think about rail networks is that there are two Class I railroads in the western United States, BNSF and Union Pacific Railroads, two Class I railroads in the eastern United States, CSXT and Norfolk Southern Railroads, one Class I railroad that runs from north to south along the Mississippi River from Chicago to Mexico the KCS and KCS (DE MEXICO?) and two Class I railroads that operate in Canada, Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railroads which span the Canadian provinces from west to east both being transcontinental railroads.

These rail networks operated approximately 162,306 miles of track (2012 data) utilizing around 24,707 locomotives and transporting approximately 364,025 railroad owned or controlled railcars, 90,502 non-class I railcars and 792,100 private (owned or controlled by banks, shippers, lessors) railcars (see Figure 1). More detailed map links of each Class I railroad are listed here:

- Union Pacific Railroad: www.up.com/aboutup/reference/maps/system_map/index.htm

- BNSF Railroad: www.bnsf.com/customers/where-can-i-ship/maps/

- CSXT Railroad: www.csx.com/index.cfm/customers/maps/

- Norfolk Southern Railroad: www.nscorp.com/content/nscorp/en/ship-with-norfolk-southern/system-overview.html

- KCS Railroad: www.kcsouthern.com/en-us/Services/Pages/WhereKCSShips.aspx

- Canadian National Railroad: www.cn.ca/en/our-business/our-network/maps

- Canadian Pacific Railroad: www.cpr.ca/en/about-cp/cp-network/Documents/cp-map-2012.pdf

Railroad Operations

Railroad operations are somewhat complicated. Railroads operate in much the same in a fashion as airlines operation. Rail operations are usually dictated by the type of traffic on a particular rail line or across a particular rail line. There are generally two types of traffic, manifest and unit train.

Manifest Traffic

Manifest traffic is described as gathering, hauling or distribution of local traffic generally accumulated as less than unit train, or that amount of rail carloads gathered together to make a train but not requiring dedicated train service. Manifest traffic requires that several rail carloads across multiple shippers be gathered together and moved on a single train. The design for moving manifest train is much the same as the hub and spoke design of the airline distribution model. A locomotive or a consist of locomotives will depart a central railyard providing service to a set number of customers during a normal shift gathering railcars that are loaded by the customers or distributing empty and loaded railcars to customers that have either order in empty railcars or are scheduled to receive loaded railcars. Generally the local train size is optimized to handle all loads and empties it is scheduled to pick up or distribute on a particular day. Local service can be scheduled daily or scheduled for select days of the week depending on local service requirements and railroad resources for the particular geographic area. Local service gathers or distributes railcars locally. After gathering railcars they are then distributed from classification yard to classification yard.

Imagine the airline distribution model. A large number of airlines land and depart Chicago O’Hare daily with most passengers going on to different destinations. Just as a passenger may travel from Denver to Chicago to Cleveland versus traveling a more direct route from Denver to Cleveland, railcars on manifest trains are moved between classification yards (much the same as airline terminals) and reclassified and accumulated at these yards for their final destination. The reason it’s important to understand this concept is that if you’re shipping less than unit train quantities your shipments (railcars) may not travel the most direct route. If you’re counting on a direct route and calculating train miles per day to account for transit times and the railcars are transported on an unanticipated route additional time could be required to move your commodity to its final destination. If you have a quota to make then you need to take into account the additional resources required. Additionally the more rail classification yards you go through the longer your shipments will take. Think of the airline route described above, it’s not the travel time between Denver to Cleveland via Chicago that takes additional time. It’s generally the reclassification process in Chicago that causes delay. Railcars are subject to this same classification delay in rail classification yards (see Figure 2).

Unit Trains

Unit train traffic operates in the same manner as the airline model as well. When an origin location has sufficient traffic that comes from one specific shipper going to one destination to one specific receiver a railroad will run a unit train. The benefit of unit train shipments are that as a shipper you get dedicated resources throughout the movement and minimal delays. A great example of this time and resource savings is again the airplane distribution model. To get to Las Vegas from Billings, MT one had a choice of going thru Denver or Salt Lake City. Now Allegiant a small airline put on service direct from Billings to Las Vegas savings six to eight hours in transit time because there was sufficient demand to require dedicated service. The plane lands in Las Vegas, distributes its passengers to the terminal, picks up a new load after minimal loading delay and heads back to Billings, the origin terminal. The unit train rail system works much the same way as the airline system. A grain train may gather a 110 railcar shuttle train (optimized for the route traveled) and depart an elevator in the middle of North Dakota and be at a terminal in Portland Oregon in three or four days. If this same terminal shipped a single railcar it may be 15 to 20 days before it would arrive in Portland. There are several examples of “trash” unit trains also running across major metropolitan areas of the U.S. to landfills.

Railroad Connections

If you review the map (exhibit X) rail lines across the US, Canada and Mexico are a spider web of lines some meeting others crossing in all sorts of geographical fashion. There is order to the chaos though. Railroads have designated connections between themselves at very specific locations. Formally known as Open and Prepaid Station List (OPSL) and now known as Official Railroad Station List is an official listing of every interchange location between every railroad in North America. These listings are generally available on each railroads web site and are worthy of researching if you’re moving freight across railroads. Another great resource is The Official Railway Guide (http://railresource.com) published by the JOC Group. This quarterly reference book shows each railroad and its connection(s) with each subsequent railroad by railroad, region and state.

Just as you’re planning airline or automobile travel it’s always a good idea to “map out” your rail shipments so you have a good idea of the route to be traveled and an expectation of the time it takes to get from an origin to a destination.

Darell Luther is president of Forsyth, MT-based Tealinc Ltd., a rail transportation solutions and railcar leasing company. Darell’s career includes positions as president of DTE Rail and DTE Transportation Services Inc., Fieldston Transportation Services LLC, managing director of coal and unit trains for Southern Pacific Railroad and directors’ positions in marketing, fleet management and integrated network management at Burlington Northern Railroad. Darell has more than 24 years of rail, truck, barge and vessel transportation experience concentrated in bulk commodity and containerized shipments. To obtain a copy of the entire Guide for Railroads, contact Darell at (406) 347-5237 or e-mail at [email protected].

Figures courtesy of Tealinc.