Many HHW programs serve businesses that routinely generate small amounts of hazardous waste. This month we will see how King County, WA has identified businesses with equity disparities and how they address the equity issue through program design.

By David Nightingale, CHMM, S.C.

This month’s HHW Corner is a follow-up from last month where we discussed the concept of diversity, equity and inclusion, often abbreviated as DEI (Waste Advantage Magazine, November 2021). We left off with the results of an HHW collection event survey by the Champaign County Environmental Stewards who found unintentional but clear gaps between who shows up at their HHW collection events versus the demographics of their citizenry. The participants were older, whiter and more often homeowners than the county as a whole. If your HHW collection program only asks for a zip code or driver’s license information from participants, you may want to expand your participant survey to see if you have gaps relative to your service area demographics.

Many HHW programs also serve businesses that routinely generate small amounts of hazardous waste. This month we will see how King County, WA has identified businesses with equity disparities and how they address the equity issue through program design. Some types of businesses are commonly owned or staffed by racial and ethnic minorities. BIPOC, another new term for your vocabulary, is often used as shorthand for the phrase: Black, Indigenous, and People Of Color in association with these minority owned/staffed businesses.

Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County Washington

In 2018, the Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County, WA (Haz Waste Program) adopted a five-year “Racial Equity Strategic Plan”.1 The Program identified the need to address racial equity because they are in a diverse and growing service area, with currently 2.3 million residents and 60,000 businesses, including Seattle and 37 other cities within King County, plus a number of tribes.

Haz Waste Program found local communities of color experience disproportionate impacts from hazardous materials exposure. Five coalition partners serve on a multi-jurisdictional Management Coordination Committee (MCC), providing oversight, strategic guidance and accountability for the Haz Waste Program. The MCC stated that, “If King County is going to be the healthy, sustainable, and livable community we aspire to have, we need to improve the outcomes for people of color by addressing the barriers they face. As the region’s demographics change, we need to plan for our future by addressing long-standing institutional barriers that inhibit success for everyone. We need to put into action our commitment to serving all people who live and work in King County and to ensuring that race is not a determinant of hazardous materials exposure. To do this we must make changes in the way that we plan, deliver services, and operate.”2

These are laudable statements and show policy leadership. The next question is “how does this translate to programs on the ground?”

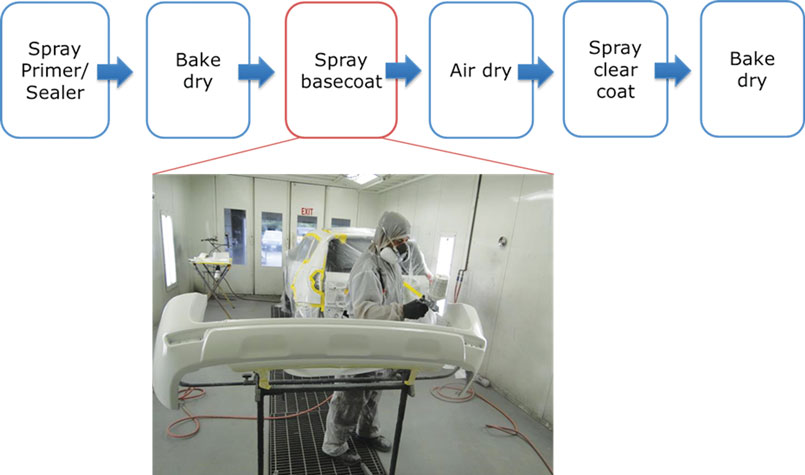

Autobody paint processes in action, spraying a waterborne basecoat. Images courtesy of Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County, WA.

King County Auto Body Project: Switching to Safer Paint

Auto body shops repair damaged cars and trucks. Automotive paints containing relatively high levels of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) are widely used in the painting process at auto body shops. The painting process involves applying a primer coat, then a basecoat, and finally a clear coat. VOCs released to the air cause ground level ozone and smog as well as a host of health issues for exposed workers.3

Short-term, acute VOC worker exposure can result in vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, lightheadedness, dizziness, fatigue, memory impairment and other effects.4 Long-term effects of VOC exposure can include liver and kidney damage, central nervous system damage, lung cancer, asthma, allergic contact dermatitis, brain damage, reproductive system damage, chemical sensitivity and emphysema.5

In King County there were no available alternatives for primer nor clear coat solventborne high-VOC painting products.6 However, waterborne, low-VOC basecoats were available and were already used by about half of the 200 auto body shops in King County. To determine if waterborne basecoats were actually safer than solventborne basecoat, this project performed a formal alternatives assessment that looked at hazardous materials and exposures, availability of alternatives in King County, cost differentials, whether alternatives performed as needed, social impacts and waste management.7

The alternatives assessment determined that waterborne basecoat paint performed at least as well as solventborne and had similar production costs. Waterborne, low-VOC basecoats still contain VOCs, such as toluene and aromatic hydrocarbons. However, during onsite exposure measurements, auto body painters using solventborne, high-VOC basecoats were exposed to higher levels of VOCs in their breathing zone than those using waterborne basecoats. Based on the results of the alternatives assessment study and exposure levels of workers, the Haz Waste Program decided to adopt a waterborne basecoat best management practice and increase the use of waterborne basecoat using financial incentives to help the shops make the conversion.

Implementation Planning with an Equity Lens

In implementing the switch to safer paints, Haz Waste Program staff followed their Equity Guide to Planning to identify if there were any racial or socio-economic disparities in the effects of this project. Auto shops were surveyed to determine primary language and ethnicity of owners and painters. This led to the development of project literature being developed for their audience who communicates most often in English, Spanish and Vietnamese. The Haz Waste Program reached out to multiethnic chambers of commerce, coordinated with a local NGO with ties to Spanish and Vietnamese body shops, and assigned Spanish-speaking staff to perform outreach.

Mr. Tae Park, one of the first dry cleaners to switch to

professional wet cleaning said, “This machine is the future.”

Results

The program ran for one year and resulted in six auto body shops converting from solventborne to waterborne basecoats—three of which were non-white owners. Four of the six shops were in more diverse areas of King County. VOCs were reduced by an estimated 1,410 pounds per year and the six shops received total reimbursement payments of just under $120,000 in financial incentives.

Less shops were converted than hoped for. However, it appears that this project helped accelerate the industry switch away from solventborne painting products in King County. Lessons learned included that you need time to get to know communities and it is difficult to get good racial equity data over the phone. Contractors should have been asked to track who was contacted, not just how many shops were contacted so follow-up can be more effective.

PERC-Free King County

Perchloroethylene (PERC or PCE) is the most common solvent used in the dry cleaning industry. Unfortunately, PERC is another VOC chemical that is very toxic to humans, causing cancer, reproductive, neurological and other health effects.8 PERC is designated as a Hazardous Air Pollutant under the Clean Air Act, a hazardous waste under the Superfund cleanup laws and regulated as a drinking water contaminant under the Safe Drinking Water Act.9

PERC is Hazardous to Dry Cleaning Shop Workers and Adjacent Communities

Workers at dry cleaning businesses using PERC are at risk of high exposure and the resulting health impacts. PERC is also persistent in the environment and is a widely found water contaminant.

Improper disposal and leaking PERC equipment has led to contamination of stormwater and groundwater.10 There are nearly 200 PERC contaminated sites in King County from dry cleaner operations. Cleanup costs can run into the millions of dollars per site. Local communities can be exposed to PERC through inhalation of vapors and drinking water contamination.11 Many water supplies in King County rely on shallow aquifer groundwater, which is vulnerable to contamination from PERC.

PERC as a Racial Equity Issue

PERC contamination from dry cleaners is a racial equity issue. More than 80 percent of dry cleaners in King County are owned by people who identify as Korean and are predominantly located in economically disadvantaged areas. When a shop has employees, they are typically Hispanic/Latino. Almost 80 percent of surveyed dry cleaners indicated that financial considerations as the primary reason they would not switch away from PERC.12 There is an alternative to PERC, which is called “professional wet cleaning” and uses a water-based system. To make the switch from PERC to professional wet cleaning costs an average of about $45,000 per shop. The capital cost of making this switch was identified through interviews and survey data as a primary barrier.13

Program Design and Results

At the start of this project there were about 100 dry cleaners in King County, the number of shops had consolidated to approximately 50 by the end of the King County project. The 2018 program goal was to get to 100 percent PERC-free dry cleaners in King County by 2025. In 2018 the Haz Waste Program started offering $20,000 vouchers per dry cleaner to switch to professional wet cleaning technology. Later, the Washington State Department of Ecology offered an additional $20,000 for shops to make the switch starting in 2019. Thirty of the 50 dry cleaners in King County had switched to professional wet cleaning equipment by the end of the King County project. Twenty-nine of these shop owners were people of color. Six-month follow-up surveys found that 89 percent of dry cleaners that have made the switch are satisfied or very satisfied with the program. Eleven shop owners reported improved health outcomes since switching to professional wet cleaning.

The Haz Waste Program stopped offering financial incentives by June 2021 when Department of Ecology ramped up to offering $40,000 to any shop in Washington who implemented the switch. An example of a local program leading the way to statewide action, as is often seen by federal action following state initiatives.

Collaboration is Key

Success of this program was due to a collaborative effort with dry cleaners and their vendors as well as working closely with federal and state regulators. Development of trusted relationships and political support from elected officials was also influential.14 | WA

David Nightingale, CHMM, S.C., is Principal at Special Waste Associates (Olympia, WA), a company that assists communities in developing or improving HHW and VSQG collection infrastructure and operations. They have visited more than 150 operating HHW collection facilities in North America. As a specialty consulting firm, Special Waste Associates works directly for program sponsors providing independent design review for new or upgrading facilities—from concept through final drawings to create safer, more efficient and cost-effective collection infrastructures. Special Waste Associates also published the book, HHW Collection Facility Design Guide. David can be reached at (360) 491-2190 or e-mail [email protected].

Notes

Their Racial Equity Strategic Plan can be found at: https://kingcountyhazwastewa.gov/en/initiatives/-/media/BEF6AE8C176041F6BB184244A3D86EE6.ashx This follows in the footsteps of the broader King County Equity and Social Justice Strategic Plan for 2016-2022, https://aqua.kingcounty.gov/dnrp/library/dnrp-directors-office/equity-social-justice/201609-ESJ-SP-Imp6GAs.pdf

Racial Equity Strategic Plan, Management Coordination Committee Commitment Letter, page 1, October 16, 2018.

Although the levels in auto body shops are often below the legal regulatory limits for breathing zone exposure, called threshold limit values, TLVs, as mentioned in the July 2021 HHW Corner article, there are chronic exposures and chronic effects or responses associated with exposures at lower levels. Chronic exposures are often repeated low dose exposure to toxic materials over longer periods of time, weeks, months or years. The negative effects can take longer to occur or accumulate before symptoms are realized—sometimes resulting in permanent damage or disease.

Larry Brown, Helping Auto Body Shops Switch to Safer Paint, Safer Alternatives in Hazardous Waste Management: Equity Based Safer Alternatives at Work and at Home, National NAHMMA Conference 2021, September 29, 2021, North American Hazardous Materials Management Association.

Ibid.

High VOCs are considered those which contain more than 3.5 pound of VOCs per gallon.

Whittaker, Stephen and Brown, Larry, Waterborne vs. Solventborne Automotive Basecoats: An Alternatives Assessment – Final Report, Local Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County, Washington, Publication Number LHWMP-0323, Seattle, April, 2019. https://kingcountyhazwastewa.gov/-/media/hazwaste/lhwmp-documents/technical-reports/automotive-paint/rsh-waterborne–vs-solvent-borne-automotive-basecoats-alternative-assessment.pdf

Scope of the Risk Evaluation for Perchloroethylene, US EPA Document 740-R1-7007, Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, US EPA, June 2017, page 11.

Ibid, page 9.

Ceballos, Diana, Fellows, Kate, et.al., Perchloroethylene and Dry Cleaning: It’s Time to Move the Industry to Safer Alternatives, Frontiers in Public Health, March 5, 2021.

Ashley Evans, PERC-free King County, Safer Alternatives in Hazardous Waste Management: Equity Based Safer Alternatives and Work and Home, National NAHMMA Conference 2021, September 29, 2021, North American Hazardous Materials Management Association.

Whittaker, Stephen, and Johanson, Chantrelle, A Profile of the Dry Cleaning Industry in King county, Washington, Public Health – Seattle and King County, publication LHWMP-0048, June 2011.

Ashley Evans, PERC-free King County, Safer Alternatives in Hazardous Waste Management: Equity Based Safer Alternatives and Work and Home, National NAHMMA Conference 2021, September 29, 2021, North American Hazardous Materials Management Association.

Ibid.