Automation

The Nuts and Bolts of Implementing A Residential Automated Collection Program

A change to solid waste automation makes sense in terms of safety, service and cost to its customers.

Marc J. Rogoff, Richard E. Lilyquist, Jeffrey L. Wood and Donald Ross

Once a feasibility report for automated collection is accepted and the approval is received from your City Commission or Board of County Commissioners, the real hard work begins. That is, trying to gain public acceptance for the changeover of the manual solid waste collection system and then to implement the plan to procure the necessary equipment to move the program forward. The City of Lakeland, FL recently commenced on implementing its residential, automated program. Some details on the program will be provided, as it has rolled out, and some preliminary “lessons learned” that will be useful for other communities just starting to explore automated collection for their customers.

Communications Plan

Experience has shown that the success of a new automated collection program is clearly dependent on deployment of a successful education and outreach campaign. It is important that every effort be used to ensure that residents have a clear understanding of how the new system will impact them. With this idea in mind, once the program was approved by the City Commission, SCS Engineers and Kessler Consultants (Tampa, FL) worked with the city’s Solid Waste and Public Information Departments to develop a proactive Communications Plan for the project.

EZ Can

The first step in the Communications Plan was to identify a brand for the program. Communication programs that had been developed in other municipalities were reviewed to identify any magic bullets as far as strategy was concerned and how this type of information could be rolled out to the city’s customers. A specific Web site, www.EZCan.lakelandgov.net, was developed by the city where customers could get information about how the program was going to be deployed over the next four years, and how they would select their specific can size (95, 65 and 35 gallon). To follow up on any potential questions, a “frequently asked questions” section on the city’s Web site was included, which covered typical questions, that city customers might have asked during the rollout of the program. A program-specific video was prepared which showed how automated collection was rolled out in a neighboring city. Lakeland’s Mayor provided some commentary about why automated collection was selected for the city and what advantages it offered both the customers and its sanitation workers in terms of safety, efficiency and a reduction in overall monthly costs. Finally, as shown in Figure 1, “billboards” were placed on city sanitation vehicles to help get the word out. This provided tremendous exposure for the program with little upfront costs.

Public Informational Meetings

One of the concerns expressed by the City Commission when the feasibility report was approved was their desire to hear from the city’s customers about the specific facets of the program. Initially, the city and SCS Engineers looked at a variety of survey tools to gauge public opinion, but decided against this approach in favor of holding an extensive series of public informational meetings in the neighborhoods where the program would be rolled out in the first year. This would provide the most detailed information about the implementation plans for the program as well as providing a vehicle to address local community concerns (Figure 2). Having the City’s Mayor as a “champion” of the program made a huge impact in this program moving forward, not only with the fellow commissioners, but also with the solid waste staff when he met with them to ease their concerns about potential staff reductions.Also, getting the Manager of Code Enforcement involved and onboard was a tall order, but vital to ensure long-term success of the new program.. At first, he was very skeptical of the program thinking that it would actually increase illegal dumping and garbage left out on the streets. After he visited his counterpart in a neighboring city, which recently had converted to automation, and was shown the difference it made in some of this city’s more historically challenging neighborhoods, he had a change of heart, especially when he saw what a difference it had made in another adjoining municipality.

Further, the city has a relatively high elderly population percentage that is typically quite vocal in the political scene, and was likewise in this solid waste automation initiative. Including a Pay-As-You-Throw (PAYT) program as part of this initiative made a real impact to this population sector when presented the fact that under the current system, these customers (typically only one or two in the household) are paying the same as the households that may have six or eight. So to those that want to cut costs, this made sense to them when this reality was laid out.

The Reasons

Implementing an automated collection program should preferably be in a series of steps through a phased in approach—adding subdivisions and areas of the city to the program over time. The financial analysis, which was conducted during the feasibility study, suggested that the city implement the program over four years. Some of the reasons for this approach included the following:

- Acclimating residents to the program organically and not concurrently. Except for the first city area to be converted, other Lakeland residents will be exposed to ongoing education and outreach programs about the new system and will have an understanding of the program when their neighborhood is ready for conversion. Also, a phased-in approach will allow the City to adjust program education based on initial feedback from the first year program residents.

- Provides an opportunity for better capital management. A phased in approach to citywide conversion would allow Lakeland to have a phased in purchase of new collection vehicles, rather than purchasing all at the same time. As vehicles age, the cost to repair increases, and at some future point, all vehicles again have to be replaced. In a phased approach, new vehicles can be purchased a few at a time each year, maintaining an average age of fleet of three to four years, while at the same time maintaining a predictable level of variable maintenance expenses.

- Today, there is a choice in automated collection vehicles and a phased-in approach. This allows the city the opportunity to test and experiment with different units on a smaller scale, rather than an initial commitment to one style, make or model. These new technologies would be examined through pilot scenarios to maximize the cost savings benefit on automation.

- A significant portion of program capital and the system’s most noticeable feature are the containers. Carts can be purchased or leased from container manufacturers who can also provide the maintenance services required. Each supplier offers a different level of specifications that should be considered, including subsequent repair and maintenance.

- Conversions would first begin in newly planned subdivisions. Newly planned subdivisions are designed with adequate turning radii and street width, and sufficient amounts of off street parking, which are conducive to automated collection systems.

Manpower

As staffing and personnel costs represent the largest portion of savings in an automated conversion, there are a number of issues that were addressed by the city during the planning phase. Automation provides significant opportunities for current solid waste employees to cross-train and advance in the division. Further, automation preserves the city’s aging workforce by reducing physical labor requirements for waste collection.

Nonetheless, these new collection vehicles will have new technology requiring specialized training for technicians in the city’s Fleet Management Division. Although this can present a challenge, it also can provide opportunities for current Fleet Division employees to cross-train and advance in the division with advanced technical certifications offered by the National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence (ASE).

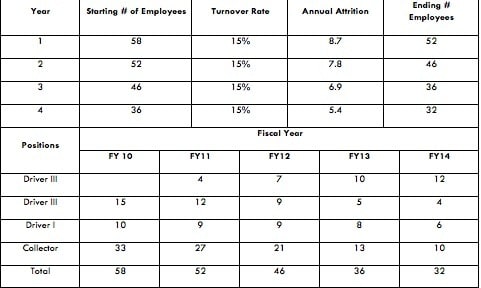

In Lakeland’s case, automated conversion is estimated to reduce the city staffing levels by approximately 20 positions, most of which are solid waste collectors. The city currently experiences a 15 percent turnover rate in residential system employees annually. Approximately 10 employees each year are replaced through attrition (retirement, termination or resignation). A phase-in approach of this system will allow the city to minimize job losses by leveraging the current rate of attrition and not filling these job vacancies. Temporary contract labor can be used to manage fluctuations and seasonal variations, until which time the positions can be eliminated altogether. Table 1 illustrates that in four years, through attrition alone, the city will have reached appropriate headcount.

Variable Pricing

Every conversion to automated collection should also consider variable rate programs as an option. These are aptly referred to as “Pay-As-You-Throw” and have a positive impact on waste diversion and recycling programs. There are various options and approaches to consider when implementing such a program. Since its introduction to residential collection in the early 1990s, variable pricing has been successfully implemented by almost 7,100 jurisdictions in the U.S. In 2007, 30 of the largest 100 U.S. cities used SMART, reaching 25 percent of the U.S. population. The programs can provide a cost-effective method of reducing landfill disposal, increasing recycling and improving equity, among other effects. The most common types of PAYT systems are:

- Variable can or subscribed can programs ask households to sign up for a specific number of containers (or size of wheelie container) as their usual garbage service level, and get a bill that is higher for bigger disposal volumes. This is a common choice in areas with fully-automated trucks using lifting arms.

- Bag or sticker/tag programs require households to buy specially-marked bags for trash; the bag price includes the cost of collection and disposal. Bags are usually sold at convenience and grocery stores in addition to municipal outlets. Other programs require households to buy special tags or stickers to place on bags or cans; pricing is similar to the bag option.

- A hybrid program uses the basic system—households keep paying a bill they’ve always paid (to the city or hauler), but instead of covering the cost of “all” or unlimited amounts of trash, it only covers 30 or 60 gallons. To get more service, special bags or stickers must be purchased (as above). This system combines existing programs and new incentives, and minimized billing and collection changes. Again, wheelies can be used for the base service (addressing possible animal issues).

- Some rural communities have drop-off programs, where customers pay by the bag or weight at transfer stations using fees, bags, stickers or pre-paid punch cards. Some haulers also offer PAYT as an option, or customers may choose unlimited service for a fixed fee.

The city’s objective in incorporating a variable pricing component to its automated collection program was to find a viable means of introducing a level of accountability to the residential customer by offering a financial incentive to place less waste out for disposal. Currently, the city relies on the Polk County Central Landfill as its sole disposal point under an Interlocal Agreement, with long-term, disposal/tipping fees set by contract. The city currently provides once per week, curbside collection of recyclables, although the collection options and potential revenues might change soon with the construction of a single-stream materials recovery facility (MRF) in Central Florida. Further, the implementation of a statewide recycling goal of 75 percent in Florida by 2020 prompted interest by the city to begin to offer variable pricing to its customers as part of the residential, automated collection program.

Lessons Learned

While every community is different, the process undertaken by the city illustrates a number of key “lessons learned”. Making the transition from a manual to automated solid waste collection program can be accomplished more easily with implementation of a detailed feasibility study, which addresses key concerns such as impacts to staffing, safety, customer service and overall costs. In this case, the feasibility report provided the necessary information and data to enable the City Commission to consider making the change to an automated collection program for Lakeland. Once the recommendations were accepted by the City Commission, the detailed communications strategy enabled the city to help address specific concerns of the public in the initial neighborhoods about customer service and choices of container size. The use of placards on the city’s collection fleet helped to get the word out in a timely fashion and with limited cost.

For example, the city has a high elderly population percentage who are quite vocal in the political scene, and were likewise in this initiative. The PAYT program made a real impact to this population sector when presented the fact that under the current system, these customers (typically only one or two in the household) are paying the same as the households that may have six or eight in it. So those wanting to cut costs, the addition of the PAYT program with solid waste automation made real sense to them when this reality was laid out.

Lastly, in this case, it was critical having the key political decision-maker in the city (the Mayor) behind the project early on to assist efforts by city staff to ensure current collection staff members that the program would be implemented through a well-conceived attrition process. These collection employees soon became our biggest advocates for the program as well as serving as “ambassadors” to the city’s customers in explaining why a change to solid waste automation made sense in terms of safety, service and cost to its customers.

Marc J. Rogoff is a Project Director with SCS Engineers. He is a nationally known expert in the procurement and operations of solid waste collection, recycling and materials recovery programs and facilities, and the economic feasibility of solid waste systems. Marc has more than 25 years of experience in solid waste management as a public agency manager and consultant. He has managed more than 400 consulting assignments across the U.S. on all facets of solid waste management including, waste collection studies, facility feasibility assessments, facility site selection, property acquisition, environmental permitting, operation plan development, solid waste facility benchmarking, ordinance development, solid waste plans, financial assessments, rate studies/audits, development of construction procurement documents, bid and RFP evaluation, contract negotiation, and bond financings. Marc serves on the International Board of the Solid Waste Association of North America (SWANA) and is a former Chair of its Collection and Transfer Technical Division. He can be reached at (813) 621-0080 or [email protected].

Richard E. Lilyquist is the Public Works Director for the City of Lakeland, FL. He is responsible for organizing, coordinating and administering the activities of the seven divisions comprised of Engineering, Construction & Maintenance, Traffic Operations, Lakes & Stormwater, Facilities Maintenance, Fleet Management and Solid Waste. Through the division managers, direction is provided to professional, technical, skilled and unskilled workers, and clerical staff involving engineering design, road construction, street and drainage maintenance, traffic system operations, lake management, solid waste collection, disposal and recycling, parking system operations, building facilities maintenance and janitorial services, and fleet management. He can be reached at (863) 834-3300 or [email protected].

Jeffrey L. Wood is the Manager of Solid Waste for the City of Lakeland. He is responsible for preparing and administrating a $13.36 million budget, 80 employees and more than 40 pieces of moving equipment. Jeffrey is responsible for ensuring timely solid waste and recycling services to all commercial and residential customers, as well as its new roll-off service. He can be reached at (941) 499-6040 or [email protected].

Donald Ross is a Senior Consultant with Kessler Consulting, Inc. where he specializes in collection and transfer operations. Prior to joining Kessler he was Solid Waste Division Manager for the City of Dunedin, FL, as well as serving as Operations Director for a number of years with Waste Management, Inc. Don is a Certified Collection Systems Manager with SWANA and is a certified instructor for the Association’s manager of collection and recycling courses. He also serves on the Board of the Florida chapter of SWANA and Recycling Florida Today. Don can be reached at (813) 971-8333 or [email protected].

Figure 1

Truck placard used by the City of Lakeland to inform and educate its customers.

Figure 2

Phase-in of the program by sectors of the city.

Images courtesy of City of Lakeland, FL.

Table 1

Lakeland’s Phase-In Plan

Table courtesy of SCS Engineers.