Between implementing a two-pronged legislative approach and creating an Organic Resource Locator tool for decision-making purposes, the U.S. could become a shining example of what cutting-edge food waste management looks like.

Jon Schroeder

Food waste in the U.S. comprises the largest portion of the municipal solid waste (MSW) stream that ends up in landfills or incinerators. According to the EPA, as of 2014, roughly 95 percent of food waste was landfilled or incinerated, which equates to 38 million tons (“Reducing Wasted”). Even though energy can be produced through conventional waste pathways, like incineration or landfilling, other beneficial opportunities from the waste product are lost, and without some major policy driving American consumers to properly sort food waste, organic waste recycling has stagnated, which does not bode well for a growing population in an ever-warming world.

Lost Opportunities

Food waste is a major problem that needs to be addressed for two important reasons. First, when waste begins to break down in landfills, anaerobic conditions are created, where microbes digest organic matter in an oxygen-deprived environment and generate methane as a by-product.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that is up to 72x more effective than carbon dioxide at trapping heat over a 20-year time frame (Platt et al., 2008). Furthermore, U.S. landfills represent the second largest industrial source of methane emissions in the U.S. (Jones, 2016), and while many landfills actively use methane capture systems, some statistics show that they only capture 20 percent of the methane being emitted (Platt et al., 2008), meaning 80 percent of the methane becomes fugitive, ending up in our atmosphere, which further exacerbates the warming crisis at our global doorstep.

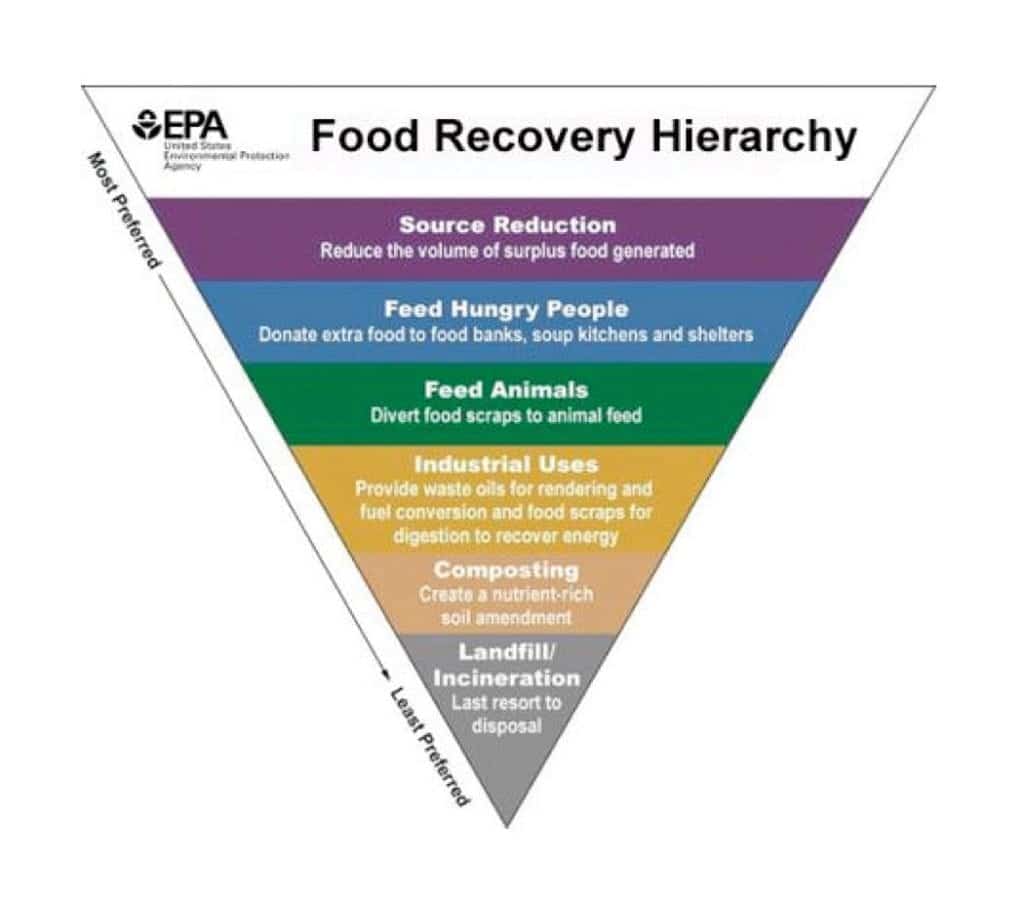

Second, food waste that is landfilled or incinerated represents a significant, but lost, opportunity. When food waste that is unopened or untouched is able to be donated, or scraps from uneaten or opened foods can be composted or anaerobically digested, benefits are brought to the masses. These benefits are ubiquitous throughout various research studies, and have even been enshrined into the EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy (Figure 1). When “food waste” is donated to local food banks or shelters, homeless or disadvantaged people are able to keep themselves fed. Composting initiatives bring benefits in the form of improved soil fertility and vitality, as compost helps retain nutrients in the soil and improves moisture retention. Anaerobic digestion yields methane, which is captured by onsite generators that convert it into heat or electricity, and a digestate coproduct, which can be spread on fields in lieu of chemical fertilizers.

Unfortunately, many of these benefits are not realized because of the lack of proper policy structure in place mandating certain percentages of waste be diverted from landfills or incinerators. As of January 2017, only five states have laws mandating organic landfill bans (“Food Scrap”). Though four of the five states use threshold requirements (commercial institutions over a certain organic waste generation rate need to comply), they still have documented goals and phase-in compliance periods stating when institutions and residents need to divert food waste to alternative pathways. While these states are politically progressive and tend to follow cutting-edge environmental best practices, it is disconcerting that the other 90 percent of states have no formalized laws on the statute books that require organic waste be kept out of landfills or incinerators. This can and should be changed.

Legislative Framework

In order to rectify growing problems associated with food waste, a legislative framework, both at a federal and state level, needs to be implemented. This legislation should be comprehensive in nature, but more specifically, should focus first on landfills, as more organic waste ends up there than in incinerators. There are two key aspects of appropriate legislation.

#1: Federal Government Mandating State Goals for Organic Waste Landfill Bans by 2025

While source reduction is the EPA’s most preferred method for addressing food waste, other protocols need to be in place that can address and handle the volumes of waste that will nevertheless be generated. Therefore, the first goal of the federal government should be to mandate that all 50 states have organic waste landfill bans or stated goals for bans by 2025. This time horizon is being used since progressive states such as Vermont have phase-in periods extending out to 2020 (“Food Scrap”). States with no recognition of the need to reduce food waste and set up infrastructure will naturally need more time. This is also assuming the federal government acts on this suggestion within a year or two.

Additionally, effective enforcement mechanisms for non-compliance need to be in place. The government should stipulate that states without proper protocols for addressing bans by 2025 pay fines to the federal government. The amount would need to be determined based on the cost of non-compliance. The government should also require that states specify a timeline in which various waste generation thresholds will be covered by the ban, until the law goes into effect for everyone, including individual households. This type of phase-in compliance would follow the precedent set forth by Vermont (“Food Scrap”).

Finally, there should be no requirement for which waste diversion pathways will be used in each state to effectively comply with the ban. Taking a note from the EU landfill directive, it is important to build flexibility into the law, enabling local jurisdictions to trial and adapt policies to best fit their individual needs (“Environmental Waste”). Ultimately, from a waste standpoint, factors such as the cost of infrastructure and revenue from end-use products (biogas and fertilizer from anaerobic digestion, humus from compost) would decide the pathways implemented. Food bank donations, which would confer tax benefits to the donator, would also increase in light of this legislation, as was illustrated by the Vermont Food Bank, which saw a 60 percent increase in donations the year after the organics ban went into effect (Leib et al., 2016).

#2: Employing a Surcharge on Landfill Tipping Fees Nationwide

To ensure financing for appropriate waste diversion infrastructure, it would be prudent for the federal government to mandate that state environmental protection agencies increase tipping fees for all operational landfills within their jurisdictions by at least 10 percent above the rates charged the year before the surcharge law was enacted. It would be up to each state government to increase the fee beyond the 10 percent standard, and this would be entirely dependent on each state’s goal of achieving a certain waste reduction amount in a specific time period.

The average landfilling fee per ton of MSW in the U.S. in 2013 was $49 (Landfill, 2015). Assuming roughly 136 million tons of garbage were landfilled that same year (“Advancing Sustainable”), the calculation follows that $680 million could be generated from a minimum 10 percent hike on the tipping fee. This calculation assumes that waste levels would stay as high as 136 million tons with the surcharge, even though tipping fee surcharges have been shown to drastically reduce waste disposal (Landfill, 2015). The point remains, however, that the leveraged fees on landfilling in the U.S. would have two primary benefits: reduced waste being landfilled and an increase in revenue, which could be funneled into food waste funds and be used to finance food waste diversion projects and fund technical assistance compliance programs. This financial policy tactic would serve more as an intermediate step needed to properly establish an alternative food waste reduction fund.

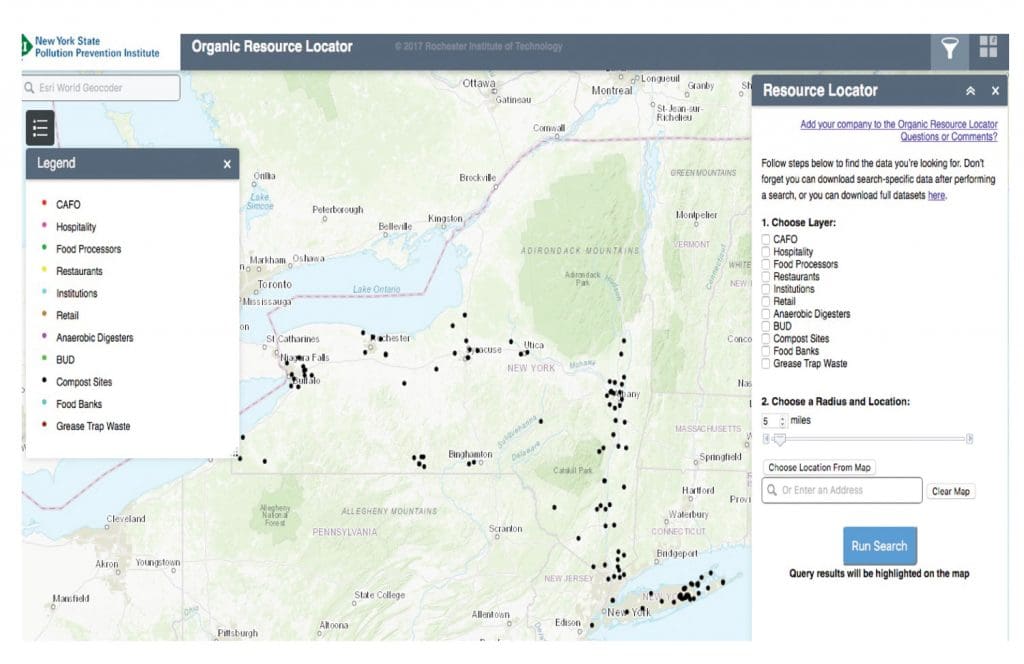

While a $680 million waste diversion fund may be large enough to staff technical assistance programs and fund grants and loans for pending food waste diversion facilities (compost sites, anaerobic digesters, food banks), the federal government, with assistance from each individual state government, would have to determine the location of various material recovery facilities before proceeding with raising additional funds. If an Organic Resource Locator (discussed below) revealed glaring gaps in spacing of adequate food waste infrastructure (excluding incinerators and landfills), and if $680 million was not enough to continue building out required sites, then more financing could be raised through various channels, including further surcharges on landfill or incineration disposal and appropriation of taxpayer funds to food waste diversion projects.

Organic Resource Locator

In addition to the legislative framework above, one of the most effective tools that could be wielded from a policy perspective is mandating the creation and maintenance of an Organic Resource Locator (ORL), a graphical interface that plots various food waste generation sites, including Concentrated Animal Feed Operations (CAFO), restaurants, hospitals, schools and recovery facilities, including landfills, incinerators, compost sites, anaerobic digesters and food banks (Ebner et al.). This tool was developed by a research team at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) to show key food waste players in New York State in order to increase the attractiveness and competitiveness of alternative food waste diversion pathways (Figure 2). Without this tool, decision-makers in government and private business would not be able to effectively site locations to handle waste loads, as they would not have any idea of the various wastes flowing throughout a geographic location.

The ORL would be an upgrade from the model assembled at RIT in that it would be a real-time feed of operational waste generation and collection sites. Legislation passed for the ORL would state clearly that any recovery facility coming online, including an anaerobic digester, compost facility, food bank or animal feed operation would need to register on the interface. The upshot is that once the site was operational, this task could be automated, so the site would recognize a new facility by itself and could update its location autonomously. Furthermore, it would be required that any closing facility, including material recovery and waste collection sites, notify the site of its intended close date, so the interface could update accordingly.

One of the main reasons the ORL is the most advantageous solution besides enacted legislation is because it directly complements a landfill ban. Once private institutions, residents and public governments see that they must comply with a food waste landfill ban, they scramble to figure out how to best accommodate their own needs, at the lowest cost and in the most efficient way.

This ORL would enable them to accurately locate proximate resources accepting organic waste. Additionally, this tool would afford private business interests as well as public government the ability to assess the organic waste landscape, and invest in or build appropriate facilities to accommodate the demand for responsibly handled organic waste.

If You Legislate It, They Will Come

Connecticut, one of the five states that has a threshold food waste ban in place, already had six sites in the permitting process, as of 2014, to handle the additional food waste from impending legislation covering businesses above a certain threshold (Williams). Massachusetts, another state with a food waste landfill ban, claims its technical assistance program and grants for facility construction have helped it achieve “zero opposition” to the law and much success with getting a large number of firms under compliance (Williams). These states show that with a little legislative willpower, and the appropriate mix of resources to aid in the successful implementation of policies, food waste diversion can be a powerful tool in reducing methane emissions from landfills and recycling valuable products, including soil amendments, digested, fertilizer, biogas and consumable products (food bank items) back into local communities. The U.S., if it implemented the two-pronged legislative approach above and created an Organic Resource Locator tool for decision-making purposes, could become a shining example of what cutting-edge food waste management looks like.

Jon Schroeder is actively looking for technology wizards and experienced food system entrepreneurs who can help bring this Organic Resource Locator to life and help advocate for legislation where need be. He holds a master’s degree in Sustainable Systems from the Golisano Institute for Sustainability in Rochester, NY, and a bachelor’s in Entrepreneurship/Sustainability from the University of Minnesota. If you are interested in helping, contact Jon by e-mail at [email protected] or connect through LinkedIn.