Community Partnerships

Home Advisors: Helping the Public Take Responsibility for Their Recyclables!

Visiting residents to talk to them about proposed services, to review contamination, and to encourage enhanced participation is essential in delivering sustainable curbside services.

Dr. Adam Read

The UK is in a period of rapid transition as Local Authorities focus their attention on the need to divert significant proportions of their household waste from landfill so that their obligations under the EU Landfill Directive are met. This cannot be achieved without the support of the residents who must accept the strategies in place and use the services on offer. Over the last decade a great deal of progress has been made in making recycling ‘the norm’ and England now has a municipal recycling rate of 40 percent with the top municipalities achieving 70 percent diversion through curbside recycling and composting programs. This rapid improvement in performance is a reflection of municipalities having learned from one another—the early innovators found services, campaigns and activities that worked and the adopters have now enhanced these programmes and refined them to suit their local geography and demographics. The key lesson learned to date is that all successful curbside collection programs are reliant on community good will and commitment, and this can only be achieved through effective communications programmes that build engagement and ownership for the schemes on offer—just like supporting your local football or basketball team, you need to feel some form of bond with your service if you are to participate regularly and effectively!

Reaching Out

The UK is now entering a period where the customer (resident) is ‘king’ and municipalities are recognizing that residents need more than an odd leaflet or poster to raise their awareness; they need direct support and encouragement to ensure their participation in curbside services, and that increasingly they need to have an input into the design and delivery of the services they are using. This is particularly pertinent given the UK Government’s commitment to ‘localism’ in decision making and their recent announcement that one London borough will be allowing residents to design a new food waste collection scheme.

One of the most effective ways of building community ownership and involvement is through the use of Home Advisors or Recycling Wardens who visit residents at home to talk to them about the service, to look at their recycling behavior and to help clarify any misconceptions that could be leading to ineffective segregation or contamination of the recycling loads. In the UK this is commonly known as doorstepping, a direct marketing approach using face-to-face contact with households (customers) on their doorstep, and it is becoming increasingly acknowledged as a highly effective method for improving participation and the quality of participation in recycling collections. Doorstepping usually involves one or more of the following:

- Raising awareness of recycling and encourage action

- Providing details about recycling collections from the home

- Increasing capture rates (the range of materials a household recycles)

- Decreasing contamination (materials that should not be put in their bag/box)

- Improving set-out (the frequency with which a household recycles)

- Improving participation (the number of households recycling)

- Providing targeted information with a personal approach

- Collecting attitudinal data on recycling

- Obtaining feedback from residents on current services.

Doorstepping usually involves volunteers, university students and new recruits who are trained in the basics of the recycling scheme on offer (the materials being collected, their destination, problems with contamination and has historic and key messages), in communications (dealing with angry residents, being supportive and helping residents to challenge their behavior without being threatening) and waste auditing (helping residents identify what is in their trash which could be recycled and what is in their recycling box which can’t be recycled). Doorstepping tends to work best when:

- The recycling service on offer is well designed and works. New participants as a result of a doorstepping campaign will not sustain their change in behavior if the current service is failing, or if their increased efforts appears to be wasted;

- Curbside collections are the most significant route for residential recycling;

- Doorstepping would not be the most effective tool to use in an authority with very limited home recycling collections that relies instead on bring sites or civic amenity sites;

- It is delivered in a high-density urban environment. Doorstepping is ideally suited to dense urban environments where distances between households are limited, or can be used to target villages or housing estates.

There are 3 distinct stages in the life cycle of a curbside recycling scheme:

- Scheme design and strategy consultation

- New scheme rollout

- Post implementation performance review and improvement

Figure 1 is a loop diagram that identifies this system in operation (the municipality is the service provider) along with an inner cycle of public engagement that is focused on ‘customer facing’ activities. It is during this cycle that the public is asked to take responsibility and ownership for their recycling scheme.

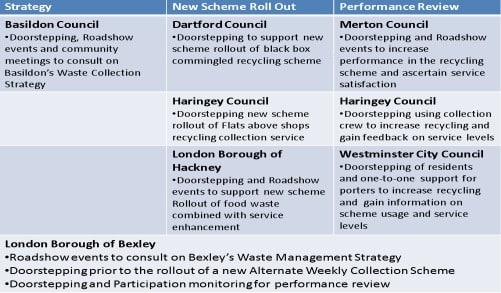

Doorstepping can play a critical part of any municipality’s communications program in support of the design, delivery and improvement of a curbside recycling scheme. Table 1 summarizes a selection of recent UK campaigns.

Examples of Doorstepping

Although doorstepping can be used to help develop strategy and test ideas with customers before a scheme is designed and launched, it is perhaps more commonly used to help roll out new collection services where a poster or leaflet is felt insufficient to fully get across the changes in service and the behaviors required. One of the key strengths of face-to-face engagement such as doorstepping is the ability to tailor responses to the individual and address key concerns and (often) misconceptions connected with recycling. This is evident from the campaign delivered in Dartford Borough Council, where the strategy decision was to switch from a curbside collection of mixed recyclables using a sack to the delivery of a black recycling box to collect recyclables. The boxes were delivered in a staged manner allowing home advisors to visit each area four weeks after their bins were delivered to reinforce key messages about the scheme and to assist residents in adjusting to the new system. The home advisors spoke to 45 percent of the households visited, ensuring a personal touch was available in the transition period. The scheme achieved a 35 percent increase in dry recycling and the use of home advisors cut the number of calls to the municipality’s helpline by 50 percent—even with a new scheme being launched.

Door-to-door promotions can also be used before program rollout to inform residents of the new scheme that is about to be launched as was the case in the London Borough of Haringey who developed a curbside recycling program for the flats above shops. Five thousand properties were visited by a doorstepper to deliver a roll of plastic sacks, an information leaflet and to help answer any questions about the scheme that was to be launched three weeks later.

However, doorstepping is most commonly used in the UK as a ‘troubleshooting’ exercise when a recycling scheme’s performance has stagnated, when contamination of the recycling is increasing or for evaluating the success of a new service. After a new scheme has been introduced or changes have been made, an existing service performance must be reviewed to ensure that the new scheme is delivering the predicted improved performance. Typical questions that need to be addressed during this evaluation are:

- Have the tonnage rates increased?

- Has participation gone up?

- Are residents satisfied with the scheme?

- What are the material capture rates?

- Are the crew operating well?

- Do any changes need to be made?

Many of these review points can be investigated without speaking directly to residents, by adopting set-out monitoring assessments of participation and by analyzing recycling tonnage data. However, to increase participation, capture rates (and hence tonnage) and to find out what area residents need additional support, it is necessary to speak to them. This was the case with the City of Westminster who targeted the worst performing streets (40 percent of all streets) with a door-to-door campaign. Not only did the home advisors promote the local collection scheme, but they also gathered feedback on problems and perceived issues. This has helped the municipality to alter their scheme and change some of their advertising to clear up problems around plastics that could and couldn’t be recycled. The other innovation with this campaign was the use of advisors from the target community, who had the same cultural background and languages. This campaign included a team who could speak Arabic, Polish, Chinese and Turkish. Being able to speak to someone in their native language often makes them more receptive to the communicated message, facilitating behavioral change.

This investigation of service usage, public acceptance and appreciation helps to complete the ‘service cycle’ by not only offering service improvements, but also helping to feedback public concerns and commentary into the ongoing service and strategy review so that the authority can improve its services and inform its communications campaigns in the years to come.

Through this approach municipalities can help to increase trust in the municipality, showing that they are listening to residents’ issues and actively trying to make service improvements on their behalf.

Meeting Residents’ Needs

It is difficult to cost a doorstep promotions campaign because each one is specifically designed for the authority in question, the service in use and the reason for the campaign. However, an average doorstep campaign that will target 35,000 residents will cost in the region of £48,000 (approx. $76,500), or approximately £1 to £1.50 ($1.50 to $2.50) per household targeted.

This is undoubtedly a large capital outlay, and may equate to the entire recycling department’s promotions budget for any particular year. But, doorstepping campaigns have been shown time and time again to reap benefits in terms of increased participation, increased tonnages, improved capture rates, increased revenue from the sale of better quality recyclables, reduced contamination levels and increased levels of customer satisfaction and residential engagement.

A well-designed and appropriate scheme is clearly important, but without effective public use these are immaterial. To ensure that the design and operation meets the resident’s needs and is effectively used, there is a real and ongoing need for service review and residential engagement and feedback. That’s where doorstepping really has a role to play.

Although as a society we are moving towards using technology as one of our primary methods of communication, the personal touch that doorstepping brings can engender ownership and should not be underestimated as an effective means of engagement. Almost every UK local authority has used some form of doorstep promotions campaign in the last decade as part of their recycling service development, and even in times of recession this is expected to be continued to ensure residents are supported and encouraged to actively take ownership of their local service—that is localism at work.

Dr. Adam Read is the Global Practice Lead for AEA’s Resource Efficiency and Waste Management Group, responsible for the technical quality of 75 staff and has 17 years of industry track-record specializing in recycling communications campaign design and delivery. He has an honorary professorship for his pioneering work on waste education and engagement and is a regular columnist in UK trade and academic journals. He can be reached at +44 (0) 870 190 2552, via e-mail at [email protected] or visit www.aeat.co.uk.

Table 1

Summary of case studies.

Table courtesy of AEA.

Sidebar

Case Study: Bexley Council

Bexley Council is a Beacon Authority for waste and recycling, recognized by the UK government for its efforts, and has achieved the highest recycling rate of all the London boroughs almost every year for the past 10 years. Prior to the design of the doorstep promotions campaign, the authors managed a set-out monitoring exercise to determine the level of public participation in half of the Council’s area. It was identified which materials were being set-out for recycling and how full the recycling containers were for all of the surveyed households. Following an analysis of the data, a targeted promotions campaign was implemented taking a series of positive and promotional messages regarding the services in use and the materials required through the curbside recycling and organics collections schemes. The main focus of the campaign was on low performing areas to encourage residents living in those areas to actively participate in the scheme and in medium performing areas to increase the level and efficiency of the residential participation, and reducing contamination levels (the wrong materials being put out for recycling).

More than 13,000 residents were involved in the face-to-face interviews where recycling scheme operation and concerns were discussed in a frank manner on the doorstep. An impressive hit rate (percentage of residents spoken to) of 39 percent was achieved. More than 91 percent of those residents spoken to supported the Council’s recycling services, and more than 3,000 new recycling containers were ordered for residents who did not have containers or they needed replacement ones (satisfied customers) or where they required increased capacity (enhanced recyclers). The doorsteppers were trained to explain to residents the reasons behind the scheme’s development, and the national need for more recycling and composting, so that they were able to answer residents’ questions effectively.

Post campaign monitoring of the same households identified a number of positive trends including a 68 percent increase in glass collected, a 19 percent increase in dry recyclables set out for collection and a 16 percent increase in paper being recycled (tonnage). In parallel the level of contamination recorded in the bins monitored reduced by 5 percent. In addition, year on year figures for the organic waste that was segregated for composting showed a rise of 11 percent (calculated using collection tonnages).