Those who generate solid waste should be required to pay for the full costs of proper, reliable, and protective management of that waste as part of their garbage disposal fees. Sufficient funds need to be collected and placed in a dedicated trust fund that could be used only for post-postclosure plausible worst case care needs for as long as the wastes posed a threat.

Anne Jones-Lee, PhD and G. Fred Lee, PhD, PE, BCEE, F.ASCE

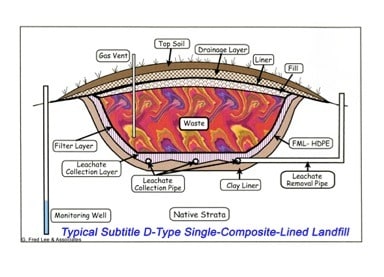

U.S. EPA RCRA Subtitle D establishes the regulatory framework and minimum prescriptive standards for the landfilling of municipal solid waste (MSW) and what are classified as “nonhazardous” solid wastes with the intent of protecting public health and environmental quality from adverse impacts of the wastes. The approach to landfilling outlined in Subtitle D, illustrated in Figure 1, page xx, can be described as creating a “dry-tomb” for the wastes—with engineered containment systems including a liner and leachate removal system, a cover to keep moisture out and a groundwater monitoring program to detect liner failure before offsite groundwater pollution occurs. The objective for the design is to minimize entrance of moisture into the landfill and to manage future formation of landfill gas and leachate so as to protect groundwater and the atmosphere from pollution with landfill-derived chemicals as long as the wastes represent a threat.

Many permitted landfills in the U.S. and some other countries are designed to just meet minimum US EPA Subtitle D prescriptive regulatory requirements for liners and covers. It has, however, been recognized in the technical literature and by U.S. EPA staff for decades that the provisions of Subtitle D are inadequate at all locations to protect groundwater resources and public health from pollution by landfills for as long as the wastes will be a threat. Among other deficiencies, inadequate attention is given to the inevitable deterioration of the engineered systems, the inability to thoroughly and reliably inspect and repair system components, fundamental flaws in the monitoring systems allowed, the truly hazardous and otherwise deleterious nature of landfill gas and leachate, and the fact that as long as the wastes are kept dry, gas and leachate will not be generated. Subtitle D “dry-tomb” landfilling does not render buried wastes innocuous; at best, it only postpones groundwater pollution. Thus, meeting the minimal requirements of Subtitle D cannot be relied upon to prevent pollution for as long as the wastes represent a threat.

Compounding deficiencies in the allowed design of “dry-tomb” landfills is the fact that current U.S. EPA Subtitle D regulatory provisions only require that a landfill owner/developer provide assured postclosure funding for 30 years. The states/counties and other political jurisdictions in which landfills are located are, or should be, justifiably concerned that private landfill companies that develop landfills will not provide reliable protection of the area water resources for as long as the wastes in the landfill will be a threat to generate leachate that can pollute groundwater—which can be expected to be hundreds of years or more. Under some regulations, if a private landfill company fails to provide adequate postclosure monitoring, maintenance and groundwater remediation when the landfill liner system fails, the responsibility for postclosure care becomes the responsibility of the people of the state, county or local community. Even if the landfill owner meets its obligations for 30-year postclosure care, the hazards of a dry-tomb landfill continue long after that period. While a local political jurisdiction, such as a county/municipality, receives permit fees and fees for hosting the landfill during the active life of the landfill, the amount of funds received can readily be far-less than amounts that will be required the after the postclosure period funds needed to properly monitor and maintain the landfill and remediate polluted groundwater. That responsibility can pose a significant long-term financial burden to the state/county and or local political jurisdiction.

Local/regional/state jurisdictions that will bear the impacts of landfill failures and to which responsibility for ad infinitum landfill care will eventually fall often do not have full understanding of the truly long-term nature of the hazards posed by Subtitle D-permitted “dry-tomb” landfills. We highlight technical issues associated with the ability of the minimum design and near minimum Subtitle D landfill to provide protection of public health and environmental quality for as long as the wastes in the landfills will be a threat to generate leachate that can pollute groundwater and release landfill gas. Two sections of our report are presented below: one of the “Key Issues Not Adequately Addressed in Subtitle D” discussed, namely “Postclosure and Post-Postclosure Care Funding,” and the “Overview of MSW Landfill Development Issues as Related to Costs of Post-Postclosure Care Costs to Public Agencies.”

In this discussion the term “post-postclosure” is used to identify the period of time beyond the required “postclosure” period during which a landfill owner is responsible for implementing and funding maintenance, monitoring, and other activities that are needed to control releases of hazardous and deleterious chemicals from the landfill to the environment.

Postclosure and Post-Postclosure Care Funding

Landfill permit applications and some operations reports provide a “standard” listing of post-closure care (monitoring and maintenance) activities and associated projected costs over the post-closure care period. The annual postclosure funding over the 30 years appears to be established based on prior years’ estimates, multipliers and adjustments for estimated rates of inflation.

A rudimentary estimate of amount of money that the state/county will need to spend for post-post-closure care in year-31 and beyond after landfill closure can be made based on the estimates of year-30 postclosure funding provisions. To the estimate based on the minimal monitoring and maintenance of the landfill covered by the year-30-based estimate must be added costs of addressing readily anticipated problems such as the repair of the landfill cover as the landfill starts, or continues, to generate leachate. Typically the landfill owners are not required to provide assured funding for repair of the cover should that be required during the 30-year postclosure period; the cover will unquestionably need repair/replacement during the post-postclosure period. Landfill cover repair will be required periodically over the time that the wastes in the landfill will be a threat.

Another major issue that can be anticipated, but is not typically included in postclosure care cost estimates, is remediation of polluted groundwater. Funding for remediation of polluted groundwater and dealing with consequences of polluted aquifers can be expected to be needed during post-postclosure. Again, over the very long period of time during which the wastes in the landfills will be a threat to generate leachate that have been required to post contingency funding in the form of a Surety Bond, Performance Bond, or other source of funding for unexpected expenditures. There is need to understand how regulatory agencies establish the contingency funding levels for the landfills. It is often not clear how these funds can be used, if at all, by county or other agency or whether they are reserved for use by the state in the event the landfill owner fails to meet its obligations during the operating and monitored 30 year postclosure period. Such contingency funding should be required for the period of time that the wastes in a landfill can generate leachate when contacted by water which will be well beyond the 30 year period of funded postclosure care.

County Host Fee

Landfill owners provide the county/local jurisdiction with permit and host fees of a specified amount per ton of waste deposited. These fees are only paid during the active life of the landfill, while wastes are being deposited. The landfill owners pay for postclosure care from funds they have generated during the active life of the landfill. The state/county/local political jurisdiction may need to fund post-postclosure care from the host fees it accumulated during the active life of the landfill, and other unspecified sources as necessary. This approach will greatly increase the amount of host fees that need to be paid to the local community/county to cover post postclosure funding needs.

Post-Postclosure Funding

An issue that will need to be addressed is whether or not the state/county administration has an understanding of long-term funding issues. From a public health/environmental quality perspective, the period during which post-postclosure care will be required for the landfills in may be indefinite; the issues that will inevitably need to be addressed during the post-postclosure period at the closed landfills are enormous. The state/county/local community should collect sufficient host fees during the active life of the landfill to establish a trust fund of sufficient magnitude to generate adequate annual interest during the post-closure and post-postclosure period to enable the state/county to pay for post- postclosure care and contingencies that will likely occur.

This will place the financial responsibility for waste management more on those who generate and deposit the wastes in the landfill and potentially less on those who happen to reside in the county and area of the landfill for decades or centuries into the future. A number of years ago, the Barons financial newsletter carried an article about the long-term liability associated with postclosure care of landfills developed by private companies under US EPA Subtitle D regulations. While those regulations obligate private landfill companies to provide assured funding for 30 years after closure of the landfill, they also contain a provision by which the U.S. EPA Regional Administrator may determine that postclosure care must continue for as long as the waste in the landfill is a threat. For example, the California landfilling regulations, in theory, obligate the landfill owner to provide postclosure care for as long as the waste in the landfill is a threat to pollute groundwater, i.e., impair its use for domestic or other purposes. California has recently adopted regulations that require landfill owners to provide postclosure care funding for 100 years which can be extended.

Overview of MSW Landfill Development Issues as Related to Costs of Post-Postclosure Care Costs to Public Agencies

The need for funding provisions for care and remediation of MSW and other types of landfills during the post-postclosure period, i.e., after the statutory minimum postclosure funding period expires, has been sorely neglected. Postclosure funding periods are typically established at a given number of years—e.g., 30 yrs—following formal closure of the landfill in an effort to hold the landfill owner responsible for aftereffects of the landfilling operation. However, such a postclosure duration designation has essentially no relationship to the period during which the wastes in the landfill will pose a threat to public health/welfare or environmental quality.

There are numerous MSW landfill siting, design, operation, closure and postclosure issues that state/county and other jurisdictions and public agencies need to evaluate and address to more reliably define the financial requirements and structure that will be needed to ensure that the owners of new, privately developed MSW landfills are held responsible for the totality of landfill monitoring and maintenance, and groundwater remediation for as long as the wastes in the landfill will be a threat to public health/welfare and environmental quality. The present practice of cessation of assured postclosure care after a given number of years, irrespective of the continued threat posed by the landfill ensures that the truly long-term post-postclosure care costs will be borne not by the waste generators or the landfill owner, but by the public in the vicinity of the landfill, in money and adverse impacts.

The fundamental problem is that the U.S. EPA Subtitle D MSW landfilling regulations are inadequate, unreliable, and misleading for the development of MSW landfills that have the ability to protect public health/welfare, groundwater and surface water resources, and air quality within the sphere of influence of the landfill (typically a several-mile radius about the landfill) for as long as the wastes pose a threat. Public landfill developers also face the same long-term impact concerns, and postclosure and post-postclosure funding needs as private landfill developers. The public entities that develop landfills (e.g., cities and counties), however, cannot walk away from the responsibility for funding landfill monitoring, maintenance, and groundwater remediation as easily as private landfill developers.

Many of the deficiencies in federal and state landfilling regulations have been well understood in the technical and regulatory communities since the late 1980s. Political considerations and administrative expedience have caused the U.S. EPA and states to ignore, dismiss or evade addressing these issues largely because it would cause the public that generates the garbage to pay significantly more for disposal/“management” of their wastes. Further, the overriding waste management strategy is to remove wastes from the densely populated urban areas and dispose of it in “remote” or “sparsely populated” areas—where there are fewer people to adversely impact—for as little money as possible. Thus, by and large, the bulk of the people who generate most of the waste are not faced with the public health/welfare and environmental quality consequences of the “disposal” of their waste. Those impacts are disproportionately inflicted upon the “fewer people” in rural environments in the vicinity of the landfills. This reality continues to lead to justified NIMBY (“not in my backyard”) attitudes and actions by those in the vicinities of proposed MSW landfills. If MSW landfills were located in urban areas where the wastes are primarily generated, the waste-generating public would become much more cognizant of and less complacent about the deficiencies in today’s U.S. EPA and state landfilling regulations in the near-term while the landfill is receiving wastes as well as in the long-term.

As long as urban dwellers who generate the garbage can have their solid wastes “disappear” from their homes, businesses, and industry at relatively low cost (a few tens of cents per person per day), and not have to experience any of the adverse short-term or long-term impacts of MSW landfills, there will be little motivation to increase the costs of garbage disposal sufficiently to enable proper management of MSW in landfills that are fully protective of public health/welfare, and water/environmental resources in the sphere of influence of the landfill. Because of the grossly inadequate provisions for post-postclosure funding for MSW landfill care for as long as the wastes in the landfill will be a threat to generate leachate and landfill gas when contacted by water, the public in both urban and rural areas will have to pay for post-postclosure care and Superfund-like groundwater remediation costs, which are likely to be several tens of millions of dollars. The current landfilling approach will not only be a major financial burden to all the people in the area of the landfill/county/state and disproportionately those of rural areas, but also result in adverse health impacts and loss of water resources in the area of the landfill.

Possible Strategies

An approach for addressing this situation could be for local agencies such as municipal, county and state agencies that face long-term post-postclosure funding liabilities to require improvements in landfill regulations over the minimum required by the U.S. EPA Subtitle D regulations to provide for technically valid and reliable landfill development and funding. Several states or parts of states have understood this situation and have adopted improved landfilling regulations, such as requiring a double-composite liner system with a leak detection system between the liners to better enable the early detection of the inevitable failures of the upper composite liner to collect the leachate generated in the landfill. As discussed herein and in our “Flawed Technology” review, the detection of leachate in such a leak detection layer would signal the need to locate and repair the areas of degradation or failure in the cover to stop the entrance of water into the landfill that generates leachate. The currently allowed landfilling approach for MSW and so-called “non- hazardous” waste does not provide the funding to make implement such an approach. Instead, as noted above and discussed in our “Flawed Technology” review, under the current approach there will inevitably be widespread groundwater pollution by landfills before deterioration and failure of landfill containment systems are recognized and addressed, consequences that may well be delayed until after the required postclosure care period has concluded. This leaves the public agencies in the area of the landfill with the responsibility for addressing the landfill and environmental consequences and the public with the public health/welfare and environmental quality impacts, as well as the financial burden of increased taxes to pay for the remediation.

Those who generate solid waste should be required to pay for the full costs of proper, reliable, and protective management of that waste as part of their garbage disposal fees. Sufficient funds need to be collected and placed in a dedicated trust fund that could be used only for post-postclosure plausible worst case care needs for as long as the wastes posed a threat. It is estimated that that approach could double to triple the cost of garbage disposal for those who generate the wastes, but it would more likely result in people’s paying the true costs for the disposal of the wastes they generate.

Anne Jones-Lee, PhD and G. Fred Lee, PhD, PE, BCEE, F.ASCE of G. Fred Lee & Associates (El Macero, CA) provide more thorough presentation of the background and context of the issues discussed herein; Dr. Lee and Jones-Lee provide extensive referencing to the professional literature on these issues. Those reports and these excerpted comments are based on Dr. Lee’s expertise and 50 years of experience reviewing the impacts of about 85 existing and proposed landfills in various areas of the U.S. and Canada. Additional information on the authors’ qualifications and experience on the matters addressed in these comments is provided at www.gfredlee.com, in the “About G. Fred Lee & Associates” section at http://www.gfredlee.com/gflinfo.html. For more information, call (530) 753-9630 or e-mail [email protected].

*Excerpted from Lee, G. F., and Jones-Lee, A., “Review of Potential Impacts of Landfills & Associated Post-Closure Cost Issues,” Report of G. Fred Lee & Associates, El Macero, CA, April (2012). http://www.gfredlee.com/Landfills/Postclosure_Cost_Issues.pdf and based on a report with literature citations: Lee, G. F. and Jones-Lee, A., “Flawed Technology of Subtitle D Landfilling of Municipal Solid Waste,” Report of G. Fred Lee & Associates, El Macero, CA, December (2004). Last updated February (2013). http://www.gfredlee.com/Landfills/SubtitleDFlawedTechnPap.pdf

References

Lee, G. F. and Jones-Lee, A., “Flawed Technology of Subtitle D Landfilling of Municipal Solid Waste,” Report of G. Fred Lee & Associates, El Macero, CA, December (2004). Last updated February (2013). www.gfredlee.com/Landfills/SubtitleDFlawedTechnPap.pdf

Lee, G. F., and Jones-Lee, A., “Review of Potential Impacts of Landfills & Associated Postclosure Cost Issues,” Report of G. Fred Lee & Associates, El Macero, CA, April (2012). www.gfredlee.com/Landfills/Postclosure_Cost_Issues.pdf

Figure 1

Typical Subtitle D-Type Single-Composite-Lined Landfill.

Figure courtesy of G. Fred Lee & Associates.