Though single-use plastics have been arguably necessary to combat the pandemic, it is important that hard-won progress toward a circular plastics economy is not reversed.

By Carli Schoenleber and Farah Lavassani

Around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly shifted plastic consumption and waste management practices (see Figure 1). Despite political and cultural movement away from single-use plastics in the past decade, products needed to fight COVID-19 (e.g., masks, gloves, gowns, testing kits) and adapt to life at home (e.g., takeout containers, delivery packaging) likely resulted in a higher proportion of single-use plastics in the waste stream. Consequently, many are concerned the pandemic accelerated negative environmental impacts from plastic waste.1 It is currently unclear to what extent COVID-19 impacted plastic waste generation in the U.S. Sseveral sources suggest the pandemic increased plastic demand, particularly for single-use plastics.10, 11, 12

It has been estimated that the U.S. created an entire year’s worth of medical waste in just two months of the pandemic,13 primarily due to greater use of disposable plastic gloves, masks, and gowns.12 Moreover, many believe single-use plastic consumption has been elevated due to heightened hygiene concerns and increased demand for household products, online orders and takeout dining.11, 14 Because of mandated stay at home orders and work from home policies, there is at least evidence that residential solid waste increased in many areas throughout the U.S., though it is still unclear how much waste has been comprised of plastic. SWANA observed a 20 percent increase in residential waste at the start of the pandemic15 and a 5 to 10 percent increase by December, 2020.16 Likewise, residential solid waste in Los Angeles (LA) increased by 15 to 20 percent.17 However, because COVID-19 shut down many commercial sectors and caused widespread unemployment, it is unclear how overall waste generation, and by extension plastic consumption, was impacted in the U.S.18 In LA, the Los Angeles Times reported commercial waste had decreased by 15 percent.17 Nonetheless, a change in the amount and type of plastic pollution was observed, suggesting an increase in single-use plastic use.

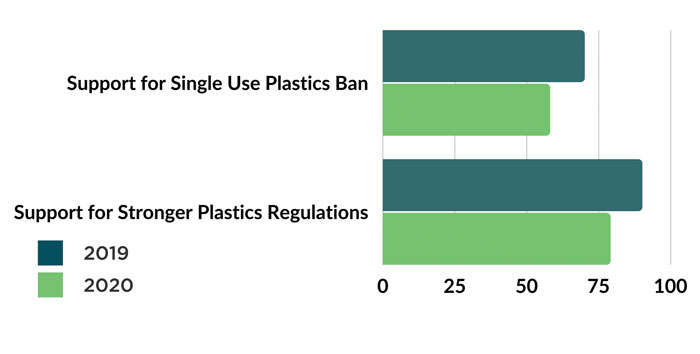

Some of these changes can likely be attributed to the suspension of laws aimed at plastic waste reduction, namely single-use plastic bag bans (see Figure 2). Given evidence that reusable bags are rarely washed and COVID-19 can survive on surfaces,21 elected officials were initially urged to suspend or delay the implementation of plastic bag ban policies to reduce transmission risk to retail and grocery workers. The Plastics Industry Association capitalized on this moment in a letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, reinstating arguments that reusable bags present a high risk of disease spread and framing single-use plastics as the safest choice.22 Throughout states and municipalities, approximately 46 plastic bag bans were delayed or temporarily suspended and 15 policies banning reusable bags were implemented (see Figure 3); as of February, 2021, about half of these plastic bag bans were still delayed or suspended and all 15 reusable bag bans had been lifted.23 California was among the many states that temporarily suspended its single-use plastic bag ban in April 2020, though the policy was reinstated by June 2020.24 Californians Against Waste reported that during this suspension, an estimated 1 billion single-use plastic bags were distributed throughout the state in May and April alone.25

cleanup (2020).

Plastic Waste Management

Nearly 150 recycling programs in the U.S. were temporarily suspended and many were cut altogether due to COVID-19.26, 27 In California, operations at several Waste Management-run Material Recovery Facilities (MRF), including the Claremont MRF in LA County, were temporarily suspended following the California stay at home order.28 Alex Helou, the City of LA Sanitation Assistant Director, reported to the Los Angeles Times in December 2020 that only five of 17 LA recyclable collection facilities had been fully operating throughout the pandemic, challenging the sorting capacity for the recycling centers that remained open.17 Consequently, thousands of tons of recycled materials were directly sent to landfills, particularly at the onset of the pandemic; in May 2020, Helou reported to KCRW that 50 to 70 percent of trucks carrying recycled materials were going directly to the landfill.29

Along with concerns of virus transmission among recycling center workers, reduced plastic recycling rates can largely be attributed to the drop in oil prices triggered by the pandemic, resulting in the lowest virgin plastic (i.e., produced from raw fossil fuels) prices seen in decades. As production costs dropped for virgin plastic, producing recycled plastic became even more expensive, with recycled plastic bottles costing 83 to 93 percent more to produce than virgin plastic bottles.4 In the same KCRW article cited previously, Alex Helou noted that the price of processing recycled materials in LA had roughly doubled from $70/ton to $150/ton.29 With greater economic incentive to use virgin plastic, demand for recycled plastic plummeted worldwide, even for the most recycled categories of reclaimed plastic (i.e., PET(#1) and HDPE(#2)).15 For example, several recycled plastic film manufacturers reported a

significant decrease in demand following California’s temporarysuspension of its single-use plastic bag ban, which also suspended requirements for plastic bag manufacturers to use 40 percent recycled plastic film.30

Yet, recycling companies in the U.S. and California had already been struggling since 2018 when China and other Asian countries widely stopped buying U.S. plastic waste. Between 2017 and 2019, U.S. plastic exports decreased by about half, from 750,000 tons to 375,000 tons.31 A 2019 report from Consumer Watchdog found 40 percent of California’s recycling centers had permanently closed since 2013.34 For years before the pandemic, it was simply cheaper to dump most plastic waste in a landfill instead of recycling it.

Mitigating Plastic Waste During and After COVID-19

Replacing Single-Use Plastics with Reusables

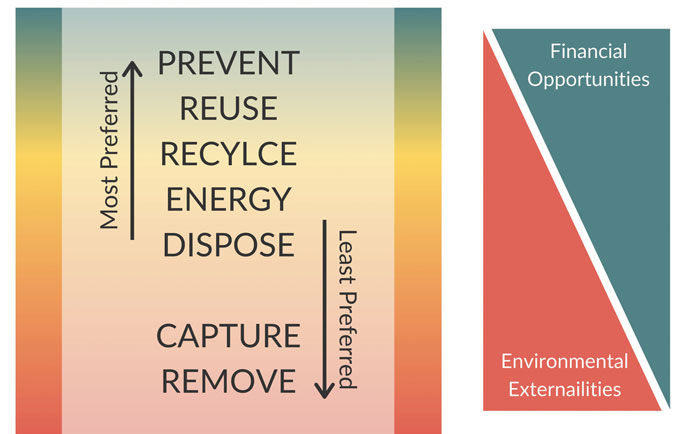

With fewer people occupying offices, restaurants and other commercial establishments due to COVID-19, an opportunity is presented to business owners and sustainability managers to implement simple but effective plastic waste reduction practices (see Figure 4). Though recycling has historically been the primary approach to sustainably manage plastics, businesses actually have the most to gain financially and environmentally by preventing plastic waste from being used in the first place (see Figure 4).38

Figures courtesy of USGBC-LA.

With this in mind, it is unsurprising that UCLA’s 2020 “Plastic Waste in LA County” report found that replacing single-use plastic food items with reusable items had “the greatest potential to reduce the negative impacts associated with plastic waste in LA County.” Furthermore, compared to bioplastic/compostable alternatives or by-request single-use disposables, reusable alternatives to food-related single-use plastics offered the greatest opportunity for operational cost savings. By investing in reusable items (e.g., dishes, utensils, coffee cups) and the infrastructure to clean them (e.g., dishwasher), available evidence suggests that businesses will break even in the first year and subsequently save thousands of dollars per year via reduced waste processing, litter clean-up and disposable item costs. As dishwashers become more energy and water efficient and the energy grid is

decarbonized, the lifetime impacts of reusables will be continually reduced over time compared to single-use disposables.33

TRUE Zero Waste Certification

To reduce plastic waste unrelated to food, business owners and facility managers would also benefit from the structure and guidance offered through the TRUE program for zero waste certification. Similar to the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED certification, TRUE offers a blueprint to increase circularity in facilities, with the ultimate goal of diverting at least 90 percent of solid waste from landfills, incineration and the environment. The program provides expert guidance to divert waste via four main avenues: reduction, reuse, composting and recycling. When systematically implemented throughout upstream supply chains and downstream waste management practices, the TRUE system reduces negative environmental impacts of waste while cutting operational costs and supporting new zero-waste markets. In addition to reusable food serviceware infrastructure, TRUE offers several strategies to reduce plastic waste generation. For example, facilities can achieve several credits within the TRUE zero waste rating system by working with vendors to reduce upstream waste. Some strategies include reducing unnecessary single- use packaging, increasing the recyclability of packaging, sending unused packaging back to vendors for reuse, and selecting vendors that embrace zero-waste or low-plastic principles.39

Education and Awareness

With evidence showing public education campaigns can reduce plastic pollution40 and increase recycling rates,41 similar campaigns should be used to dispel myths around COVID-19 and single-use plastics. Based on our review of how COVID-19 shifted plastic consumption and management above, we recommend campaigns focus on two false beliefs: 1) single-use plastics are safer than reusable alternatives and 2) all plastics accepted in our recycling bins actually get recycled.

Are Single-Use Plastics Safer than Reusables?

Because many single-use plastic bag laws were suspended or delayed for COVID-19 related safety reasons, it is important to provide awareness on the safety of reusable items. In the case of suspending single-use plastic bag bans, health experts were quick to point out there was no evidence that single-use plastic bags were less likely to spread COVID-19 than reusable alternatives.21 In fact, a 2020 study concluded reusable grocery bags presented a very small risk of COVID-19 transmission compared to human-to-human contact via respiratory droplets.42 Moreover, more than 125 health experts around the world signed a statement in June 2020 that reusable items can be similarly hygienic if they are washed and/or disinfected before use.43 Neither the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have indicated reusable items present any public health risks when it comes to mitigating COVID-19.44 Furthermore, some experts have questioned the underlying assumption that single-use plastic bags are reliably sanitary. Dr. Kate O’Neil at the University of California Berkeley maintained that in comparison to sterile gloves and masks used in a doctor’s office, single-use plastic bags are not held to the same hygienic standards and thus cannot be assumed to be sterile.45 Before the pandemic, California was headed in the right direction by enacting AB 619 in 2019, a law that now requires restaurants to allow customer use of clean reusable cups and containers.46

Do All Recyclable Plastics Get Recycled?

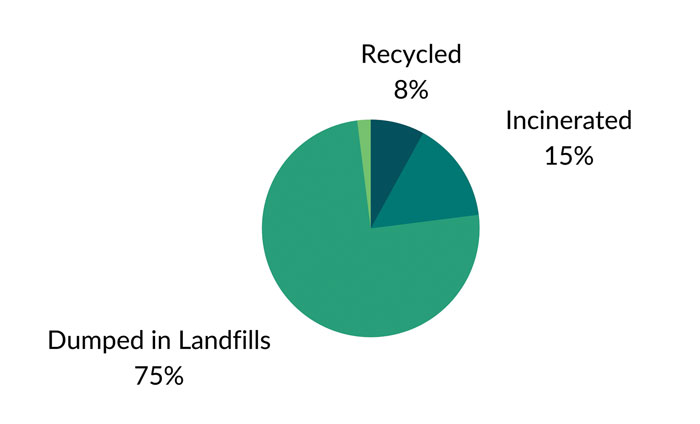

Another belief that should be targeted is the false perception that plastic placed in a blue bin will actually get recycled. In reality, the amount of plastic recycled is not just dependent on what can technically be recycled but rather on demand for recycled plastic materials and local availability of recycling technology. Despite the fact that most plastics are recyclable, many MRFs will not recover and recycle single-use plastic products due to difficulty in sorting and the high likelihood of food residue contamination.33 As noted previously, only 8 percent of plastics in the U.S. get recycled. Likewise, in LA County, only PET(#1) and HDPE(#2) plastics are commonly recycled (e.g., milk jugs, detergent bottles and drink bottles) and plastic resin types 3, 4, 6, and 7 (e.g., medicine bottles, yogurt cups, plastic bags), along with all single-use plastic foodware, are likely to head straight for a landfill.33

Part of the publics’ confusion around plastic recycling has been attributed to plastic resin codes (e.g., #1=PET) stamped on most plastic items, which also includes the three arrow recycling symbol. According to 2020 reporting from National Public Radio, the plastic industry began lobbying to put this misleading symbol on plastic items in 1989, allegedly to subdue public concern around the environmental impacts of plastic. Unsurprisingly, once this symbol became standard, consumers began throwing plastic items in their blue bins that local recyclers could not actually sell or reclaim.47 To combat this misconception, recyclers and municipalities should work together to educate consumers on what resin codes actually translate to recyclability in their local area. In theory, if the public is aware plastic recyclability does not necessarily translate to plastic recycling, people may be more apt to reduce consumption of single-use plastics and adopt reuse practices (see Figure 5).

Reducing and Recycling Disposable PPE

It will also be important in the short term to minimize the negative impact of disposable PPE (e.g., masks, gloves) as these materials are difficult to recycle and negatively impact the environment.48,49 In addition to harming marine ecosystems when littered, a study from the University College London estimated disposable masks have 10 times the climate change impact than reusable cloth masks.50 Given multi-layered cloth masks have been recommended by the CDC to prevent community spread of COVID-19,51 encouraging the public to replace disposable masks with reusable cloth masks is a sound option to both mitigate plastic waste and slow the spread of COVID-19.

For disposable, PPE that is unavoidable and not used in a medical setting, the environmental impact of PPE can be reduced by recycling it through programs like Terracycle and Rightcycle. Recognizing PPE cannot be recycled through most public services, Terracycle offers a mail-in Zero Waste Box that makes it easy for facilities to recycle single-use PPE such as masks, gloves and safety glasses.52 Similarly, non-medical facilities that use Kimberly-Clark PPE can use the RightCycle program to mail back used plastic gloves, glasses and protective clothing, which are then recycled into plastic pellets and used to manufacture new consumer goods. The RightCycle program has been successfully implemented in facilities such as breweries, zoos and science laboratories.53

Policy Mechanisms

Much like other environmental crises, government interventions will likely be necessary to fully shift to a circular plastics economy.2 Prominent policy ideas include taxing virgin plastic, subsidizing recycled plastic and investing in recycling technology.

Taxing virgin plastics or difficult to recycle plastics is a commonly cited strategy to target single-use plastics.56, 57, 58 Currently, the price of virgin plastic does not reflect the true cost of plastics’ negative impacts on the environment and society (e.g., harm to marine ecosystems, GHG emissions, litter clean-up), thus taxation could help raise funds to mitigate these impacts. Taxation also has the potential to reduce unnecessary plastic packaging in manufacturing, drive demand for recycled plastic, and encourage innovation in recycling technologies.59,60 Similarly, landfill tipping fees could be increased to make recycling a more economic choice.61 As there is a lack of applied research on positive or negative consequences of plastic taxes, care should be taken to ensure taxes would not increase consumer good prices for low-income communities; a plastic tax dividend returned to taxpayers may help mitigate this issue.56

On the other hand, subsidies or tax breaks could help make recycled plastic less expensive to produce and thus more economically competitive with virgin plastic. Beyond subsidizing recycled plastic and easily recycled plastics, subsidies could also be directed towards efficient recycling facilities, thereby incentivizing innovation towards more effective sorting technology.62 Emerging technologies (e.g., machine learning, chemical recycling) exist, but further investments are needed to scale up recycling of mixed plastics beyond PET (#1) and HDPE (#2)63 as well as compostable bio-based plastics that currently lack adequate industrial composting infrastructure to bring to scale.64

State and Local Plastic Policies

Unfortunately, the California Circular Economy Pollution Reduction Act (Senate Bill 54) was rejected by California lawmakers in 2020. This policy aimed to drastically reduce single-use plastic waste by requiring all food- and packaging-related single-use waste to be recyclable or compostable by 2032, aiming for a 75 percent reduction in waste from single-use products. If passed, it would have been the strictest single-use plastic law in the U.S., but there is some hope it will be reconsidered in 2021.65 On the bright side, California lawmakers passed Assembly Bill 793 in 2020, which requires all plastic bottles to contain at least 15 percent recycled plastic by 2022, 25 percent by 2025, and 50 percent by 2030, and allocates funding for recycling infrastructure.66 Moreover, since Assembly Bill 1884 was enacted in 2018, food vendors throughout California have only been allowed to distribute plastic straws upon request.67

Locally, LA County similarly approved a plastic straw and stirrer ordinance following AB 1884.68 In 2019, the City of Santa Monica implemented a Disposable Food Service Ware Ordinance, that prohibits all non-marine-degradable food service ware, including all types of plastic.69 Lastly, LA County indicated they were in the process of creating a policy to target food-related single-use plastic waste immediately before the pandemic, however, as of February 2021, no details on such a policy have been released.70

Investing in Infrastructure

Because comprehensive waste data throughout the pandemic has yet to be released, it is still unclear as to what extent the pandemic impacted overall waste and plastic waste generation in the U.S. and LA. As it stands, it appears the pandemic increased use of single-use plastics due to heightened demand for PPE, takeout dining, online orders and household products. Data is similarly decentralized when it comes to plastic waste management, but available evidence suggests the pandemic further hampered the recycling industry’s ability to

reclaim plastic waste, largely due to the drop in oil prices that shifted demand away from recycled plastic towards virgin plastics.

To both reduce the use of single-use plastics and increase plasticrecycling rates during and after the pandemic, we recommend that leaders invest in infrastructure to support reuse practices in commercial buildings to reduce use of food-related single-use plastics, the most impactful plastic waste category in LA County. The TRUE zero waste rating system may be particularly useful for facilities to streamline more sustainable plastic waste management systems. Other solutions include dispelling public misinformation around the safety of reusables, decreasing the use of disposable masks, and increasing recycling rates for PPE.

Though single-use plastics have been arguably necessary to combat the pandemic, it is important that hard-won progress toward a circular plastics economy is not reversed. From GHG heavy plastic production processes to the profound impact of plastic waste on our oceans, with or without a pandemic, it is critical that our society move away from the mainstream linear plastic economy and its associated negative environmental and economic impacts. | WA

Carli Schoenleber, USGBC-LA, is a Los Angeles based freelance writer with 10 years of experience in sustainability and environmental science. She holds a M.S. degree in Forest Ecosystems and Society from Oregon State University with a research focus on conservation psychology. Specializing in a range of complex sustainability topics, she is currently writing a sustainable real estate textbook series for the Verdani Institute for the Built Environment.

Farah Lavassani serves as the Marketing Manager of the U.S. Green Building Council, Los Angeles. After studying Social Work with an emphasis on both Childhood Development and Urban Planning, Farah pursued higher education in environmental sciences with a focus on marketing. With more than five years of experience in non-profits, forming her own organic clothing line, and managing a sustainability lifestyle blog, she is proud to bring her dual experience with advocacy and marketing skills to USGBC-LA. Farah is a LEED Green Associate, ENV SP, and Living Future Ambassador with primary interests in forming sustainable infrastructure for our communities and optimizing sustainable strategy + programs for the professional world.

For more information, contact Ben Stapleton, Executive Director, USGBC-LA, at [email protected].

This excerpt is part of the white paper of the same name, which appears in whole on the U.S. Green Building Council-Los Angeles Chapter’s website: https://usgbc-la.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/USGBC-LA-Whitepaper-Series_-Covid-19-Single-Use-Plastics-1.pdf

Acknowledgements

USGBC-LA Executive Director: Ben Stapleton

LASER Program Manager: Becky Feldman Edwar

LASER Leadership Committee: Ben Stapleton – Executive Director, USGBC-LA; Nurit Katz – Chief Sustainability Officer, UCLA; Lisa Day – Manager Environmental Sustainability, Disney; John Marler – VP Energy and Environment, AEG; Lisa Collichio – Director Sustainability, Metrolink; Maria Sison-Roces – Manager Corporate Sustainability Programs, LADWP; Gabe Olson – Clean Energy Strategy, SoCalGas; Natalie Teera – VP Sustainability and Social Impact, Hudson Pacific Properties; Rick Duarte- Sustainability, Metropolitan Water District; Tamara Wallace – Sustainability Manager, Cal States Office of the Chancellor.

Special thanks to: Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, Denise Braun (All About Waste), Stacy Sinclair (LA Metro), Rebecca Rasmussen (City of LA), and Erin Lopez (USGBC-LA).

Notes

To see the full list of footnotes included, visit https://usgbc-la.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/USGBC-LA-Whitepaper-Series_-Covid-19-Single-Use-Plastics-1.pdf (Page 16 – 19)

Notes

1.Sarkodie, S. A., & Owusu, P.A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on waste management. Environment, development and sustainability, 1–10.

2. Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). The new plastics economy: Rethinking the future of plastics & catalyzing action.

10. Glaun, D. (2021, February 17). The Plastic Industry Is Growing During COVID. Recycling? Not So Much. PBS.

11. Prata, J. C., Silva, A. L., Walker, T. R., Duarte, A. C., &Rocha-Santos, T. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic repercussions on the use and management of plastics. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(13), 7760-7765. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c02178

12. Adyel, T. M. (2020). Accumulation of plastic waste during covid-19. Science, 369 (6509), 1314-1315. doi:10.1126/science.abd9925

13. Cutler, S. (2020, April16). Mounting Medical Waste from COVID-19 Emphasizes the Need for a Sustainable Waste Management Strategy. Frost & Sullivan.

14. Patrício Silva, A.L., Prata, J. C., Walker, T. R., Duarte, A. C., Ouyang, W., Barcelò, D., & Rocha-Santos, T. (2021). Increased plastic pollution due To Covid-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations. Chemical Engineering Journal, 405, 126683. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126683

15. Love, B. J., &. Rieland, J. (2020, September 06). COVID-19 is laying waste to many US recycling programs. The Conversation.

16. Nemo, L. (2020, December 22). How local waste and recycling leaders are grappling with coronavirus-driven budget pressures. Wastedive.

17. Calfas, M. (2020, December 5). A struggling recycling industry faces new crisis with coronavirus. Los Angeles Times.

18. Naughton, C. (2020). Will the COVID-19 Pandemic change waste generation and composition?: The need for more real-time waste management data and systems thinking. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 162, 105050.

21. Nemo, L. (2020, April 2). Single-use plastic bag supporters cite coronavirus risks in reviving sanitation concerns over reusables. Wastedive.

22. Radoszeweski, T (2020, March 18). Plastics Industry Association COVID-19 letter. Politico.

23. Product Stewardship Institute (2021, February 28). COVID-19 Impacts on U.S. Plastics Policy, as of 2-28-21.

24. Martichoux, A. (2020, June 23). Plastic bags are banned again in California as COVID-19 order expires. ABC7 News.

25. Californians Against Waste. (2020, June 22). Governor Newsom authorizes roadmap for return to reusable bags.

26. Bothwell, L. (2020, June15). Lessons from Republic & RRS on operations duringCOVID-19. Waste 360.

27. Waste Dive Team. (2021, February 28). Where curbside recycling program shave stopped in the US. Wastedive.

28. Crunden, E. A. (2020, May 19). Waste Management resumes all California MRF operations after COVID-19 concerns. Wastedive.

29. Wells, C. (2020, May 7). Waste in some landfills is down, but so is recycling. Here’s why. KCRW.

30. Staub, C. (2020, June 24). California reinstates bag ban and PCR requirements. Plastics Recycling Update.

31. O’Neill, K. (2019, June 5). As more developing countries reject plastic waste exports, wealthy nations seek solutions at home. The Conversation.

33. Coffee, D., Faigen, M., & Milani, J. L., & Richardson, C. (2020, January). Plastic waste in Los Angeles County: Impacts, recyclability, and the potential for alternatives in the food service sector. UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

34. Tucker, L. (2019, March). Halfanickel: How California consumers get deposits ripped off on every bottle deposit they pay. Consumer Watchdog.

38. Dijkstra, H., Van Beukering, P., & Brouwer, R. (2020). Business models and sustainable plastic management: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120967.

39. TRUE. (2020, June). TRUE rating system updated June, 2020.

40. Willis, K., Maureaud, C., Wilcox, C., & Hardesty, B. D. (2018). How successful are waste abatement campaigns and government policies at reducing plastic waste into the marine environment? Marine Policy, 96, 243-249.

41. Sidique, S. F., Joshi, S. V., & Lupi, F. (2010). Factors influencing the rate of recycling: An analysis of Minnesota counties. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 54(4), 242-249.

42. Hale, R. C., & Song, B. (2020). Single-use plastics and COVID-19: Scientific evidence and environmental regulations. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(12), 7034-7036.

43. Greenpeace (2020, June 16). Over 125 health experts sign onto statement on the safety of reusables during COVID-19.

44. Upstream. (2021). Reuse vs single-use: Safety.

45. Vann, K. (2020, March25). COVID-19 puts BYO coffee cups on hold, but sanitized reusable systems could fill the void. Wastedive.

46. Lamb, C. (2019, July19). New California Law Sets Protocol for Reusable Food and Drink Containers. The Spoon.

47. Sullivan, L. (2020, September 11). How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled. National Public Radio.

48. Roberts, K. P., Bowyer, C., Kolstoe, S., & Fletcher,S. (2020, August14). Coronavirus face masks: an environmental disaster that might last generations. The Conversation.

49. Parkinson, J. (2020, September 13). Coronavirus: Disposable masks’ causing enormous plastic waste’. BBC News.

50. UCL Plastic Waste Innovation Hub. (2020). The environmental dangers of employing single-use face masks as part of COVID-19 exit strategy.

51. Center for Disease Control. (2020, November 20). Science Brief: Community Use of Cloth Masks to Control the Spread of SARS-CoV-2.

52. Terracycle. (2021). Safety equipment and protective gear- Zero waste box.

53. Kimberly-Clark Professional. (2021). Right cycle by Kimberly-Clark Professional.

56. Simon, M. (2020, August 4). Should Governments Slap a Taxon Plastic? WIRED.

57. Hewgill, D. (2018, May 15). Tackling the plastic problem: Using the tax system or charges to address single-use plastic waste. Local Authority Recycling Advisory Committee.

58. Prata, J. C., Silva, A. L., DaCosta, J. P., Mouneyrac, C., Walker, T. R.,Duarte, A.C., & Rocha-Santos, T. (2019). Solutions and integrated strategies for the control and mitigation of plastic and microplastic pollution. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2411.

59. Stahel, W. R. (2013). Policy for material efficiency—sustainable taxation as a departure from the throwaway society. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 371(1986), 20110567.

60. Bruvoll, A. (1998). Taxing virgin materials: an approach to waste problems. Resource, Conservation & Recycling, 22 (1-2), p. 15-29.

61. U.S. EPA. (2014, January). Scoping Study for Additional Economic Indicators. U.S. EPA Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery.

62. Vanapalli, K. R., Sharma, H. B., Ranjan, V. P., Samal, B., Bhattacharya, J., Dubey, B. K., & Goel, S. (2021). Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Science of The Total Environment, 750, 141514.

63. Peszko, G. (2020, April7). Plastics: The coronavirus could reset the clock. World Bank Blogs.

64. Ducat, D. (2018, August 16). Bio-based plastics can reduce waste, but only if we invest in both making and getting rid of them. The Conversation.

65. SB.54—California Circular Economy and Plastic Pollution Reduction Act, California Legislature 2019-2020 RegularSession, (2020).

66. AB.793—Recycling: plastic beverage containers: minimum recycled content, Legislative Councel’s Digest, (2020).

67. AB.1884—Food facilities: single-use plastic straws, Legislative Councel’s Digest, (2018).

68. Los Angeles County Public Health. (2019). Single-use plastic straws/stirrers.

69. City of Santa Monica Office of Sustainability and the Environment. (2020). Disposable foodware ordinance.

70. Los Angeles County.(2020).L.A. County to take big bite out of plastic pollution.