Finding the optimum tradeoff between protection and comfort.

By David Miller

I remember the summer the Deepwater Horizon accident in the Gulf of Mexico caused serious disruption to the coastline of some of the nicest beaches in the U.S. My family had booked a vacation on Okaloosa Island, which is just down the road from Destin, FL. We took our chances and proceeded with our plan despite the ominous possibility than an oil slick could slither over our beachfront paradise at any moment and ruin everything.

The oil never did show up. We had lovely weather and a noticeably uncrowded week that summer on the sugar-sand beaches of the Florida panhandle. Though there were fewer vacationers, we shared the beach with a different class of beach visitor. A small army of workers had been sent to clean up the anticipated tar balls and any other bi-products of the accident. The odd juxtaposition of remediation workers in yellow hazmat boots milling among bikini-clad sun bathers as they sought out anything suspicious in the sand to pick up and stick inside their empty plastic hazmat bags is an enduring memory we have of that vacation.

Classifying the Risk

The image of those yellow hazmat boots came to mind when I was thinking about all the different reasons waste workers might have to don protective outfits in the course of their duties. Waste cleanup can involve nuisance risks or it can require full body protection and SCBA respirators. Whatever the risk, there is a disposable suit available to meet the need. The tricky part can be determining what the risk is and what PPE is required to meet it.

There is a price to pay for miscalculating the amount of protection required.If you trivialize the risks, you could leave your team vulnerable to contamination. If you err too far on the side of caution, your team will endure more discomfort than they need to. Your costs will also rise exponentially as you increase levels of protection.

Image courtesy of HUB Industrial Supply.

Common Materials

Most disposable coveralls are constructed of nonwoven synthetic fabric. As they increase in protection levels, different materials will be laminated together to increase strength, decrease permeability and possibly make it flame retardant. The most basic suit will be constructed of a single layer of spunbond polypropylene and will be breathable and relatively comfortable. It is commonly used by workers in paint spray booths or as a basic barrier in nonhazardous cleanup operations in a mostly dry environment. It is not liquid-proof, nor does it resist tears nearly as well as more complex compositions.

Another popular material is known by its acronym SMS. This is two layers of this same spunbond polypropylene with a layer of meltblown polypropylene in the middle. This composition is still comfortably breathablem, but resists tears and punctures and has improved resistance to liquids. SMS suits are found in use in laboratories, industrial applications, as well as sanitation and medical fields.

Tyvek® is made from high density polyethylene and sees a lot of use as a disposable garment in the medical and hazmat industries. It is more durable than SMS, allows air transpiration, but resists liquids and abrasions.

Increasing the protective barrier beyond Tyvek means increased layering of protective films and polymers that will increase cost and decrease comfort. If the environmental hazards presented require complete isolation from chemicals or toxic vapors, then breathability must be dispensed with altogether.

Coverall Construction Details

Another factor in selection of coveralls is the construction details. There are choices to be made whether the garment will come with integrated booties and a hood or whether elastic cuffs around wrists and ankles will be desired. Most suits will feature a long front zipper closure, and the more protective ones will also provide a strip of tape along the zipper flap to seal the zipper seam completely.

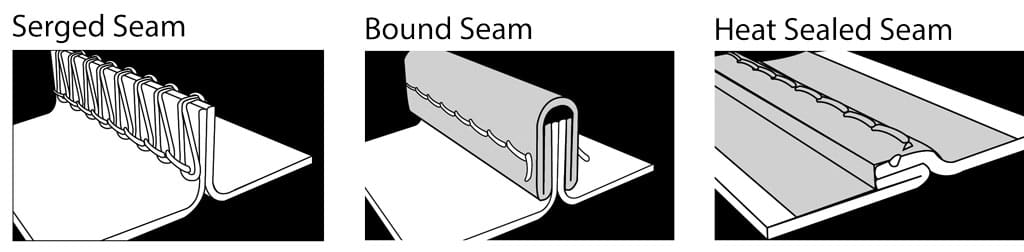

Another construction consideration is the detail of the garment’s seams. The most common treatment is serged seams, but if more security is required, a bound seam will hold the garment together with a lower failure rate. For highly sensitive situations, the seam is sewn and then sealed with heat sensitive tape.

If the term “gusset” appears in the specifications of a suit, this refers to an additional amount of fabric sewn into areas like the underarms or crotch to allow more freedom of movement.

Other Considerations

Fitting the user to the proper size garment makes a difference in the comfort to the user. There should be room enough to perform all movements without stressing the seams of the garment, but not so much room that movements become unwieldy. Users should receive training on how to don a suit and how gloves and boots and facial gear should be placed in relation to the suit. When hazardous substances are involved, detailed training on the proper removal and disposal of the garment is also highly important.

As is the case with all safety gear, your supplier is a wonderful resource to assist you in selecting the best options for your specific needs. The more information you can provide to help your supplier assess your needs, the better they are able to propose the optimum solution.

David Miller is the Waste Industry Manager for HUB Industrial Supply (Lake City, FL). He is a Certified Safety Professional and works with managers to effectively implement and manage PPE and MRO programs in the waste industry. He may be reached at [email protected]. HUB Industrial Supply is an Applied MSSSM company.